Download PDF via DOI:

https://doi.org/10.51480/compress.2024.7-2.757

The Roles Performed by Polish Journalists Covering 26th UN Climate Change Conference

Role pełnione przez polskich dziennikarzy podczas relacjonowania 26. Konferencji Klimatycznej ONZ

Abstrakt

Abstract

Keywords

- climate change, COP26, journalistic role performance, Konferencja Klimatyczna ONZ, media coverage, przekaz medialny, role dziennikarskie, UN Climate Change Conference, zmiana klimatu

Media coverage on climate change

Because the media is one of the most important sources of information, it may serve several functions, such as education or mobilization (McBride, 1980; McQuail, 2007). According to agenda-setting theory, it also affects public opinion by priming and framing. McCombs (2004) indicated that the media not only increases interest and gives meaning to the issues it informs, but it may also trigger certain actions in its recipients (e.g., the fuel crisis in Germany in 19731). The media is especially important in the context of dealing with issues like climate change. The media can indicate that such a problem exists and how it affects common people’s lives, explaining what it encompasses or what actions people can take. However, including people who represent a different point of view than the scientific one may cause people to devalue it, believing that science and the threat of climate change are not certain. Ultimately such media postings may cause people to deny the problem: Donald Trump’s statement “climate change is a hoax” was quite popular (Beattie & McGuire, 2019). However, journalists representing individual media outlets also transmit information related to climate change, such as floods and fires or events during which those problems are discussed—like mentioning the UN Climate Change Conferences. Claudia Mellado (2015) indicated six journalistic roles: watchdog, loyal facilitator, service, infotainment, civic, and disseminator-interventionist.

Previous COPs grabbed media attention (both traditional media and online, including social media) because of their news value (Galtung & Ruge, 1965; Harcup & O’Neil, 2016). Not only can debate be sparked in left-wing or liberal media (COP15), but the same news can appear in the conservative press. Sajna (2012) noted that even if media outlets presented different perspectives (“serious problem” or “scientists’ conspiracy”), none questioned the idea of fighting the threats caused by climate change. Moreover, scientists can not only participate in the COP as an expert, but they can also use social media to publish their opinions. Those who participate in the COPs can use their social media accounts for live reports during the conference just as journalists do, by posting photos or updates. Those who do not attend can focus on disseminating information, like scientists have traditionally done (Walter et al., 2017).

UN Climate Change Conferences

The threats resulting from climate change and its potential scenarios for the future are indicated in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports. Although this phenomenon can be the result of several causes, such as “natural internal processes or external forcings such as modulations of the solar cycles, volcanic eruptions” (IPCC, 2018, p. 544), the current climate change is caused predominantly by human actions. Scientists agreed with this statement in a scientific consensus because of the observed warming since the mid-20th century (Cook et al., 2016; Stocker et al., 2013). Those human actions are related to the emission of greenhouse gases, like what results from the combustion of fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas. Fossil fuels are the basis of the modern world. They are used for electricity, heating, transportation, and many items in every household. Unfortunately, the destruction of ecosystems by polluting, deforestation, or littering accelerates the negative effects of climate change.

Such issues are raised during COPs, which themselves are supposed to be one of the answers to climate change. During this annual event, participants discuss problems related to this phenomenon, report their achievements and challenges, and try to work out an agreement among delegations, like the Paris Agreement in 2015. The first conference was held in Berlin in 1995 (United Nations Climate Change, n.d.). In 2021, COP was held for the 26th time and took place in the United Kingdom in Glasgow. The event raised high expectations due to the delay: although COP26 was planned for 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic made it impossible to organize it. This caused a delay in addressing the more visible problems caused by climate change, such as raising sea levels as a threat to such island countries as Tuvalu. The minister for foreign affairs of that country, Simon Kofe, recorded his speech to COP26 wearing a suit and standing in the seawater in Tuvalu to show how real a threat climate change is (Reuters, 2021). COP26 was divided into two parts. The first part, from October 31 to November 2, was when the power elite participated (the heads of state, ministers). The second part, from November 3 to November 12, was when delegations’ experts discussed the problems and worked out an agreement.

During the 26th UN Climate Change Conference, not only did the official part of the debate occur, but many activists also arrived in Glasgow to show their disagreement with the power elite’s delay in making decisions that could mitigate the threats of climate change, such as shifting away from using and burning fossil fuels. Other objections to officials were impediments to non-governmental organization participation in the conference (Zielona Interia, 2021a), the presence of representatives of the fuel lobby in some of the state delegations (Zielona Interia, 2021b), and the creation of a traffic jam of private jets over Glasgow by COP26 participants (Interia, 2021).

Methodology

Sample

For the purposes of this study, I conducted a quantitative media content analysis of the roles performed by Polish journalists while covering the 26th UN Climate Change Conference. The subject of the research was news items disseminated by selected Polish news media outlets—TV broadcasters and online portals. These two media types are those most often used by Polish citizens (Eurobarometer, 2023). The particular media outlets were selected using four factors: nationwide reach, frequency of published content (every day), popularity (viewing/reading), and type of medium according to financing source (public/commercial). Thus, the research material comes from three main Polish TV news broadcasts: one public service channel, TVP1 (Wiadomości [News]), and two commercial ones, TVN (Fakty [Facts] and Polsat (Wydarzenia [Events])4. Of all the news items published during the period of study, the following categories were excluded: announcements of programs broadcast by a television station (e.g., entertainment), materials of the portal’s partners, ads, games, links to films on VOD, culinary recipes, or content of recipients (e.g., Internet forum, links to accounts on the photo portal).

Research tool

The research tool used in this study was a codebook. It was based on the theory of journalistic role performance by Claudia Mellado (2015). Some of the categories used in this study were original categories from the codebook developed for the Journalistic Role Performance Project (second wave) initiated and coordinated by Mellado. However, I specifically modified and adapted some original categories for the purposes of this study. The codebook consisted of three parts: general information, sources, and journalistic roles. The first part used categories such as date, headline, importance of the news, geographic frame, topics, and news values. The second part focused on sources, for example, type of source, the presence of an expert, identification of the expert, and compatibility or incompatibility with scientific consensus. The last part was dedicated to the examination of the performance of the journalistic role.

Research questions

For the purposes of this study, I formulated three research questions.

- RQ 1: Which of the roles performed by journalists appeared most often in the analyzed news?

Based on Mellado’s theory of journalistic role performance (2015), the codebook distinguished categories related to the six roles she recognized, watchdog, loyal facilitator, service, infotainment and civic, as well as interventionist versus detached reporting. In an analyzed news item, at least one indicator describing the selected role had to be coded to consider the role as present (e.g., the presence of a call to action category as one of the interventionist indicators meant that in this news item an interventionist role was present).

- RQ 2: Was the educator role performed by journalists during COP26?

Because of the topic discussed in this study—climate change—and its educational potential, I added educator to the six roles proposed by Mellado (2015). Among the roles that media may play, the educational function could be significant in such a topic. Moreover, one of the tasks of the Polish public service media (such as TVP1) is to “serve the development of culture, science, and education, with particular emphasis on Polish intellectual and artistic achievements,” what is mentioned in the Broadcasting Act (Ustawa o radiofonii i telewizji, 2022, p. 36).

The educator role is related to such aspects as presenting scientific publications (e.g., reports, research results), explaining phenomena occurring in the environment, or informing and educating about laws and regulations. In this study I applied all these indicators to the problem of climate change.

- RQ 3: What sources did journalists cite in the analyzed news?

The last issue in this study refers to the sources cited by journalists. The aim was to establish a type of source and examine statements made by that source to determine the extent to which they were compatible with scientific consensus. Another goal was to trace which sources were recognized as experts and whether they were real experts or only people journalists wanted to present as experts. Finally, I explored what types of experts were cited most often.

Findings

Presence of the COP26 in the news media

During the research period, 19,412 news items were published in the six selected Polish media outlets (395 TV news items and 19,017 online news items). After selection using the key words “cop26”, “climate”, “conference”, “summit”, “Glasgow”, and “UN”, I analyzed 167 COP26-related items with the use of the codebook; 16 items came from TV news (4% of all TV news items), and 151 items came from online media (1% of all online news items). Moreover, about 42% of the COP26 items were published between October 31 and November 2, the days during which the power elite (heads of state, prime ministers, etc.) participated in the event. That is 75% of all the COP26 TV items (12) and 39% of all the COP26 online media items (58).

Although the total number of items does not show strong media attention being paid to the COP26 issue, the media outlets took some “extra” actions regarding this event. First, all three TV broadcasters under study sent journalists to Glasgow, so they were able to provide their reports right from the field. Second, online information websites showed their engagement too. Polish media outlets Onet and WP cooperated with Greenpeace’s action and aired an appeal to sign a petition and a countdown timer designating the last moment to stop using coal. However, from October 31 to November 12, 2021, some important domestic events grabbed much of the Polish media attention. There was a migration crisis on the Polish-Belarusian border, protests against the anti-abortion law in Poland after the death of a pregnant woman in a hospital in Pszczyna (protest participants considered the anti-abortion law to be the cause of the woman’s death), an increase in the incidence of COVID-19 in Poland, All Saints Day6.

Journalistic roles in the media coverage of COP26

The first research question was related to roles performed by journalists. Six of the roles included in the codebook used in the study were presented by Claudia Mellado (2015). Some of the categories in this research tool concerned one role; some combined several. For the purposes of this study, if at least one of the indicators assigned to the role is coded, then the role is present in particular news item.

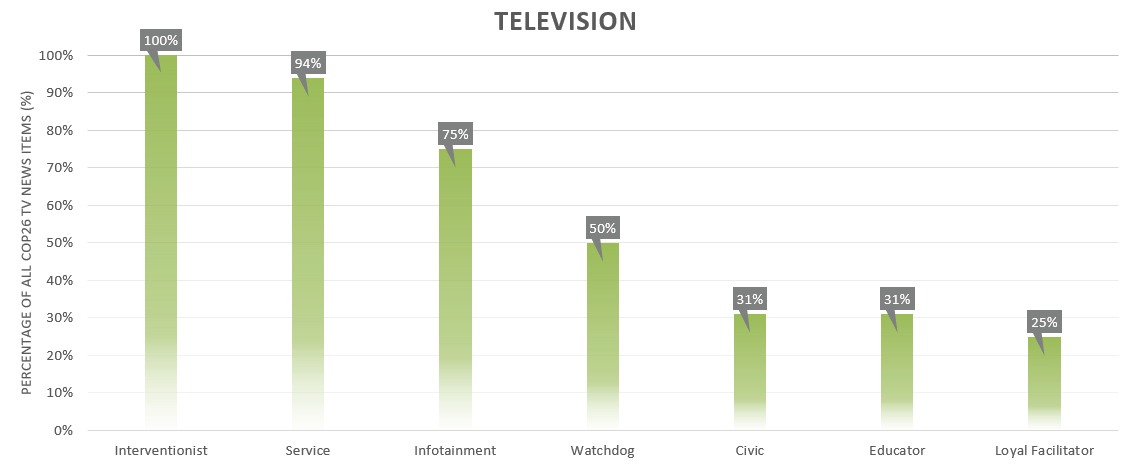

All six journalistic roles were represented in the news that was analyzed, both on television and online. In the TV news the clearest role was interventionist, whose indicators were coded in all COP26 news items (100%). Those journalists made their presence known in these news stories mostly by presenting their opinions next to information about the discussed topic (approximately 81%), using qualifying (evaluative) adjectives (approximately 69%), and calling the elite to action (approximately 44%). Other roles often performed by journalists were service (approximately 94%) and infotainment (75%). The service role grew from the impact on everyday life of information presented in the news. Infotainment appeared mostly while presenting current or potential consequences of climate change (as well as people’s reactions to included examples of catastrophes) or people’s emotions during protests. Next, the roles of watchdog (50%) and civic (31%) were identified. The loyal facilitator role was the least frequently coded (25%). Figure 1 illustrates the occurrence of individual journalistic roles in the television coverage of COP26.

Figure 1. Roles performed by journalists while covering COP26 in the television media outlets, from October 31 to November 12, 2021 (TVP1, TVN, Polsat).

Source: Own calculations

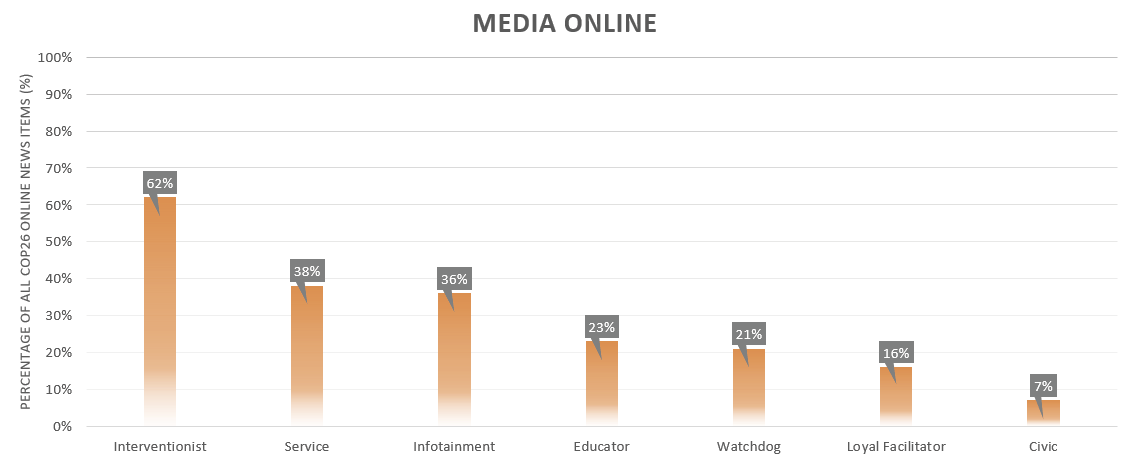

The online media outlets (Figure 2) were in a similar situation to the TVs. An interventionist role’s indicators were coded most often (62%). Next were service (38%) and infotainment (approximately 36%). Then came watchdog (21%) and loyal facilitator (approximately 16%). The civic role was identified least frequently in media online news (approximately 7%). In two news items, no indicator related to any role was encoded.

Figure 2. Roles performed by journalists while covering COP26 in the online media outlets, from October 31 to November 12, 2021 (Interia, Onet, WP).

Source: Own calculations

Educator role performed by journalists

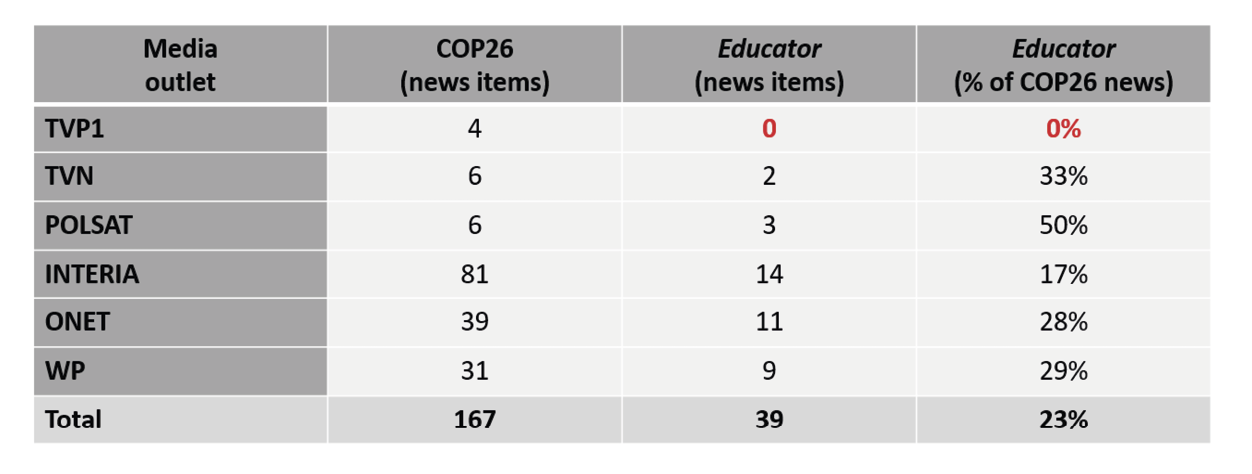

For the purposes of this study, I added educator to the roles indicated by Claudia Mellado (2015). This role is related to presenting information from scientific publications, explaining phenomena related to climate change and the environment, or informing their audience about changes in laws related to climate change and the environment. Such indicators were encoded in the COP26 news items published by five media outlets: TVN, Polsat, Interia, Onet, and WP (Table 1). Educator was not noted in TVP1, which is one of the public service media outlets in Poland, so the presence of educational information could be expected. The educator’s indicators were coded in 31% of TV news items (Figure 1) and approximately 23% of online news items (Figure 2). It was identified most often in Interia with 14 items, but the largest percentage share was noted in Polsat—50% (Table 1).

Table 1. The presence of the educator role in the media coverage on COP26, from October 31 to November 12, 2021 (TVP1, TVN, Polsat, Interia, Onet, WP)

Source: Own calculations

To determine the presence of the educator role, I selected two indicators. The first was presenting information from scientific publications. An example is from Onet:

The latest comprehensive research report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – the highest scientific authority on the subject – outlined only one scenario in which 1.5 is possible. According to it, global CO2 emissions will fall this decade and reach net zero around mid-century. But even then, the world will exceed the 1.5-degree threshold before sinking below again with the help of large-scale efforts to suck carbon from the atmosphere (Broniatowski, 2021)7.

This example contains a reference to one of the most important documents on climate change, the IPCC’s report.

Another indicator, explaining phenomena related to climate change and the environment, was coded in the Interia, specifically in the Zielona Interia. The journalist was indicating why methane is such a dangerous gas and how it impacts the greenhouse effect. The news item contains information about an agreement related to methane by COP26 participants:

Methane is the second most important greenhouse gas, after carbon dioxide, contributing to global warming. Although it has a higher potential to retain heat in the Earth’s atmosphere, it decomposes faster, so reducing its emissions could have a quick impact on stopping global warming (Zielona Interia, 2021c)8.

Sources cited in the COP26 news

The sources that appeared in news related to COP26 were also analyzed. Because of the event’s multifaceted significance (environmental, political, societal, economic, and energy-related), I considered numerous types of sources. The sources appeared in almost all of the COP26 news items (approximately 96%). Representatives of the power elite were most frequently cited by journalists in both TV and online media outlets: 75% of TV news and 54% of online news. The second most frequently cited type of source was directly related to the media. For television, it was a journalist who was at the scene (50%), but in online news it was a foreign media outlet (33%). The most common TV sources included an expert (50%) and an activist (approximately 44%). But apart from what was mentioned earlier, the sources cited most frequently in online media were an NGO’s representative (approximately 14%) and an activist (approximately 10%).

An important part of this research was identifying the presence of experts and who they were. According to the findings, in the case of television, the following experts were coded: scientists, journalists, activists/NGOs, and politicians (three times “other” was chosen). In the media online news, scientists, activists/NGOs, and economists appeared as experts (“other” was chosen two times).

Conclusions

The 26th UN Climate Change Conference was a global event during which participants reported on their country’s climate politics (achievements and failures), discussed problems, planned new actions, and attempted to reach an agreement. COPs are usually held once a year, but COP26 was postponed due to COVID-19 (it was planned for 2020). Because of this and because scientists and activists have stated that the 2020s are a critical decade for the future of the Earth, the event was eagerly anticipated by people from all over the world as well as being deemed media-worthy.

The analysis of the media content led to several conclusions although from a qualitative perspective, it can be said that the media paid little to no attention to this event. News related to COP26 included only 4% of TV news and 1% of online news. The UN Climate Change Conference was mentioned in the period under study in all surveyed media outlets. In addition, all six media outlets highlighted COP26 in some way. In the case of television, each station dispatched a reporter to Glasgow, the location of the event. I have indicated examples of standups or live reporting. Furthermore, all information websites exposed environmental protection issues, such as the promotion of the Greenpeace action in which they participated.

Second, the results of the study showed that all journalistic roles proposed by Claudia Mellado (2015) and the addition of educator were performed in both television news and online media news. Only in one media outlet, TVP1 (television), was the educator role not coded. This was unexpected because of the public service nature of this Polish media outlet. Furthermore, three of the most frequently coded roles were the same in TV and online media—interventionist, service, and infotainment. I identified an interventionist role in all television COP26 news (for online media it was 62%). The presence of the educator in five of six analyzed media outlets showed that there is indeed educational potential in the climate change topic and that journalists can be an important voice in climate and environmental education.

Finally, the sources appeared in approximately 96% of analyzed news related to the event. Among the most cited sources were the power elite: 75% of TV news and 54% of the online news. This indicates the importance of the political meaning of the event and the role of power elite representatives in making decisions related to addressing the global threat of climate change.

References

Beattie, G., McGuire, L. (2019). The psychology of climate change. London and New York: Routledge.

Broniatowski, M. (2021). Dlaczego szczyt klimatyczny COP26 nie uratuje planety [Why the COP26 climate summit will not save the planet]. From: https://wiadomosci.onet.pl/politico/dlaczego-szczyt-klimatyczny-cop26-nie-uratuje-planety/tezl1h3 (14.06.2024).

Cook, J., Oreskes, N., Doran P. T., et al. (2016). Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming. Environmental Research Letters, 11, 048002. DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/048002.

COP26 (2021). Climate change is the most important issue of our time, and the stakes could not be higher… From: https://x.com/COP26/status/1379773940873187328?s=20 (14.06.2024).

Eurobarometer (2023). Media & news survey 2023. From: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/api/deliverable/download/file?deliverableId=89601 (14.06.2024).

Galtung, J., & Ruge, M. (1965). The structure of foreign news: Presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus crises in four Norwegian newspapers. Journal of Peace Research, 2(1), 64–90. DOI: 10.1177/002234336500200104.

Greenpeace (n.d.). What are the solutions to climate change?. From: https://www.greenpeace.org.uk/challenges/climate-change/solutions-climate-change/ (11.12.2024).

Harcup, T., & O’Neill, D. (2017). What is news?. Journalism Studies, 18(12), 1470–1488, https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2016.1150193.

Interia (2021). Wielka Brytania: W Glasgow utworzył się korek prywatnych odrzutowców [Great Britain: Private jets jam in Glasgow]. From: https://wydarzenia.interia.pl/zagranica/news-wielka-brytania-w-glasgow-utworzyl-sie-korek-prywatnych-odrz,nId,5618504 (14.06.2024).

IPCC (2018). Annex I: Glossary. In: J.B.R. Matthews (ed.). Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty (pp. 541–562). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157940.008

McBride, S. (1980). Many voices. One world. From: https://waccglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/MacBride-Report-English.pdf (14.06.2024).

McCombs, M. (2004). Setting the agenda. The mass media and public opinion. Cambridge: Polity Press.

McQuail, D. (2010). McQuail’s mass communication theory. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore and Washington DC: Sage Publishing.

Mellado, C. (2015). Professional roles in news content. Six dimensions of journalistic role performance. Journalism Studies, 16(4), 596–614. DOI:10.1080/1461670X.2014.922276.

Reuters (2021). Tuvalu minister stands in sea to film COP26 speech to show climate change. From: https://www.reuters.com/business/cop/tuvalu-minister-stands-sea-film-cop26-speech-show-climate-change-2021-11-08/ (14.06.2024).

Sajna, R. (2012). Planet Earth on the eve of the Copenhagen Climate Conference 2009: A study of prestige newspapers from different continents. Observatorio Journal, 6(2), 071-083, https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS622012367.

Stocker, T. et al. (2013). Climate change 2013: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. From: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2017/09/WG1AR5_Frontmatter_FINAL.pdf (14.06.2024).

Szymczak, J. (2023). Pożary w Grecji. „Największa tego typu katastrofa w UE” [Fires in Greece. “The largest disaster of this kind in the EU”]. From https://oko.press/pozary-w-grecji-najwieksza-tego-typu-katastrofa-w-ue (14.06.2024).

UNESCO & MECCE (2024). Education and climate change: Learning to act form people and planet. From: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000389801/PDF/389801eng.pdf.multi (11.12.2024).

United Nations (1992). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. From: https://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/background_publications_htmlpdf/application/pdf/conveng.pdf (14.06.2024).

United Nations (2023). Press Conference by Secretary-General António Guterres at United Nations Headquarters. From: https://press.un.org/en/2023/sgsm21893.doc.htm (10.12.2024).

United Nations Climate Change (n.d.). Conference of Parties. From: https://unfccc.int/process/bodies/supreme-bodies/conference-of-the-parties-cop (14.06.2024).

Ustawa z dnia 29 grudnia 1992 r. o radiofonii i telewizji Dz.U. z 2022 r. poz. 1722 ze zm. [Broadcasting Act of 29 December 1992] (2022).

Walter, S., De Silva-Schmidt, F., & Brüggemann, M. (2017). From “knowledge brokers” to opinion makers: How physical presence affected scientists’ twitter use during the COP21 Climate Change Conference. International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 570–591. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/6016/2254 (12.06.2024).

Zielona Interia (2021a). Problemy organizacji pozarządowych na COP26 [NGO problems at COP26]. From: https://zielona.interia.pl/polityka-klimatyczna/news-problemy-organizacji-pozarzadowych-na – cop26,nId,5624427 (14.06.2024).

Zielona Interia (2021b). BBC: Najwięcej delegatów na COP26 to lobbyści przemysłu paliw kopalnych [BBC: Most delegates at COP26 are fossil fuel industry lobbyists]. From: https://zielona.interia.pl/polityka-klimatyczna/news-bbc-najwiecej-delegatow – na-cop26-to-lobbysci-przemyslu-paliw,nId,5632593 (14.06.2024).

Zielona Interia (2021c). Koalicja na rzecz redukcji emisji metanu coraz większa [Methane emission reduction coalition grows]. From: https://zielona.interia.pl/polityka-klimatyczna/news-koalicja-na-rzecz-redukcji-emisji-metanu-coraz-wieksza,nId,5620142 (14.06.2024).

1 In the autumn of 1973, German media outlets published an increased number of negative opinions about the fuel supply and those who evaluate a situation as a crisis (due to price increase in Arab countries or boycotts against the US and the Netherlands). In November the federal government forbade using cars during specified periods and changed the speed limit on highways. News in German media outlets led to fear of a possible lack of fuel in the country. Consequently, people wanted to ensure supplies and bought more fuel than before. Those actions created a fuel crisis and a real situation in which access to fuel was limited (McCombs, 2004).

2 The television news items chosen for analysis (published in Wiadomości, Fakty, and Wydarzenia) were collected by Content Analysis System for Television (CAST) functioning at the Faculty of Political Sciences and Journalism at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań (Poland).

3 The online news items were collected by web plugin available in Google Chrome. For the purposes of the study, twice a day (between 11:00–11:30 a.m. and 11:00–11.30 p.m.) main websites of Interia¸ Onet, and WP (as well as their subpages dedicated to climate change and environmental protection issues) were scanned and saved with links to each item. It should be noted that those websites might be a little bit different for each user due to algorithms.

4 Because of the specificity of the Polish language, all forms of these keywords were considered in the research, for example, “climate” as a verb klimat or “climate” as the adjective “klimatyczny”.

5 All Saints Day is celebrated on November 1st, and it is a day off in Poland. Each year many Poles visit their relatives’ graves in many parts of the country. On that day the news in the Polish media is related to holiday celebrations, road traffic, so-called “cemetery candle action” (along with information on the number of drunk drivers or road accidents), and memories of famous people who died in the past year.

6 The Independence March is a cyclical event organized for Polish Independence Day (November 11). This march is controversial because of the behavior of some participants (vandalism or burning the EU flag), and it is associated with the nationalist movement. Each year leads to a debate between supporters and opponents of the event. In 2021 a court in Warsaw initially prohibited the march, but it ultimately took place as a state event.

7 Own translation.

8 Own translation.