Russian Assessments of Anniversary of Hundred Years of the Great October Socialist Revolution

Abstrakt

Abstract

Keywords

- Anniversary of Great October Social Revolution, politics of memory, polityka pamięci, rocznica Rewolucji Październikowej, Rosja, Russia

Introduction

Common picture of the past is one of the main pillars of the identity of modern society. Politics of memory cannot exist without efficient communication between state and society as the attitude to some historical moments substantially depends on actual political discourse in a country. However, the subject of politics is not the past itself, but social beliefs about the past based on so-called collective memory – “socially shared cultural knowledge of the past, which is formed on different sources and is characterized by fundamental incompleteness and selectivity” (Efremova & Malinova, 2018, p. 116). Thus, the picture about a specific event is possible to be distorted by simplifications and emotional factors with a view to facilitate its perception by the group members as something “obvious”. It is worth bearing in mind that the collective past may be affected by certain interpretations. The elites often tend to pursue the objectives goals not necessarily forming a specific concept of the past: they might seek to legitimize their own power, justify their decisions or influence values, attitudes, beliefs and behaviors of the society (ibid., p. 117). It is therefore appropriate to conclude that politics of memory is directed at the present and future, serving as an attribute of social influence by means of forming cultural infrastructure, educational policy and legislative regulation.

According to historian Peter Carrier (1996, p. 435) “commemorations, whether occurring „naturally” after a predictable lapse of time, or else organized in order to diffuse and implant a specific interpretation of the past” basing on “elements of both the original event and the new context within which the commemorative „event” takes place”. Therefore, commemoration activities in terms of collective memory concept may serve as a pretext for political use of the past and have different interpretations in the context of the current political agenda (Efremova & Malinova, 2018, p. 119). The process of selection of what is to be remembered and forgotten is important in this regard. Remembrance refers to what is essential in retrospect, whereas forgetfulness – to what appears to be no longer useful details. A case in point might be not merely historical facts, but also emotional connection to them, where any mismatch can be the basis for conflicts of “memory”. Sociologist Iwona Irwin-Zarecka (1994, p. 90) shares these views stating that remembrance might have its own infrastructure: “parts of it might be continuously in use, while other parts remain unattended for long stretches of time”. Monuments, museums, holidays, literature and arts may exemplify the infrastructure serving as a symbolic source, which meaning often changes over time.

Particular attention should be given to commemoration practices such as important dates on the calendar – holidays or anniversaries. Their standardization and repeatability may be considered as a reliable socialization tool. However, it requires updating with time, for younger generation needs new cultural representations to form an emotional bond to the past (Ensink, 2003, pp. 10–11). By way of instance, commemoration of historical events also needs proper media coverage to transfer historical knowledge and collective memory. It is worth recalling that although media might be an important attribute of shaping picture of the past, they may omit some details and/or present different elements of history from a certain perspective. This may influence the way of perception of the present and future about history, identity and memory by the citizens (Bałdys & Piątek, 2016, pp. 67–68). It should be noted, however, that the process of recreating an objective picture of the events of that time in its entirety is complex, for its presentation consists of many factors, which are subject to shifts in interpretations by different actors. Thus, drawing on theoretical framework, in this article it is supposed to consider how the October Revolution is remembered in today’s Russia and what it symbolizes from the viewpoint of such selected actors as politicians, citizens and media. The method of secondary data analysis was chosen for the purposes of framing the official Russian discourse of politics of memory and public opinion regarding the anniversary of the revolution. Presentation of Russian media discourse in the context of the October revolution was based on secondary analysis of the “Center for Russian Political Culture Studies” report discussing the results of media monitoring. Moreover, the study was conducted on the basis of a content analysis of the narratives appeared in the evening news program “Vremya” on the main Federal channel “Pervyy kanal” on the day of the celebration the anniversary of the October Revolution (November 7, 2017). The analysis was based on the following questions: Total duration of the program? Duration of the narratives regarding the revolution and the 1941 parade? How the revolution and the 1941 parade were presented? The data was coded and assessed in accordance with the needs of categorizing the answers. Research results are described in the following sections.

Great October Social Revolution: changing perspectives

Numerous issues appeared in connection with commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the October Revolution. Before considering the contemporary understanding of the event, it is necessary to give a quick overview of changing perspectives of its perception from the moment of its inclusion in the Soviet history.

The October Revolution is known to be an armed insurgency started in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) in 1917 on November 7 (October 25)1 that brought Bolshevik Party to power. This date turned into an official state holiday in 1918. Its commemoration became a military parade gradually growing into the main holiday of the USSR. However, it was relevant only in terms of historical context that was political in nature: the holiday may have emphasized the significance of new political order being a consequence of revolutionary events (Anikin, 2014, p. 140). Until the end of Stalin’s regime, the October revolution served as a general myth about genesis of the USSR where prerevolutionary past turned into the prehistory of the rebellion.

A political discourse in terms of politics of memory has been changing in 1950–1980s in the USSR. In this period, one could observe a process of romanticization of the 1917 event by politicians: it was “glorified as a Leninist project of ‘genuine’ communism, from which Stalin allegedly retreated, defaming the revolution with bloody and unreasonable violence” (Narskiy, 2017, p. 79). At the same time, the Victory over Fascism of the Soviet Union served as a justification for the time of Stalin’s terror. After the collapse of the USSR there was a redefining of the revolution several times in the 1990s and 2000s. Igor Narskiy (2017) argues that “the October Revolution for the first time officially fell into the shadow of war, when November 7 was declared the Day of Military Glory in 1995”. The holiday itself may have become mourning for all victims of the civil war. However, since it is possible to consider the revolution from different perspectives, a question may have risen here: how do different actors understand this event in contemporary Russia in terms of the 100th anniversary of the October events in 2017?

Contemporary political discourse

Authorities’ interpretation of history has always played one of the most important roles in society’s self-determination and self-identification. October Social Revolution was celebrated every year on November 7 in the Soviet Union. “The education of Soviet citizens was based on the fact that due to October they live in a completely new type of state” (Saprykina, 2016, p. 63). However, after the dissolution of the USSR Russia experienced changes of emphasis and restructuring of strategic approach in official Russian discourse related to the anniversary of the October revolution (Kochneva & Fredovna, p. 18).

During post-soviet period, the authorities have been committing to the policy of desovietization “aimed at displacement of high meanings of “November 7” from collective memory of Russians” (ibid.). In 1991 common parades and demonstrations were cancelled in relation to changes in the political situation that entailed transformation of symbolic discourse. In 1992 the government decided to reduce number of days off (one on November 7 instead of two on November 7–8) devoting to the memory of the revolution. Until 1995 the holiday used to be called as “The day of 1917 October Revolution” (O dnyakh voinskoy slavy i pamyatnykh datakh Rossii, 1995), however, in 1996 in accordance with the Presidential decree No. 1537 “About the day of concord and reconciliation” it was claimed that “1917 October Revolution radically influenced the fate of our country. In an effort to continue to prevent confrontation, in order to unite and consolidate Russian society, I decide: 1. To declare a holiday on November 7 as The Day of Consent and Reconciliation. 2. To declare 1997 to be the year of the 80th anniversary of the October Revolution, the Year of Concord and Reconciliation” (O dne soglasiya i primireniya, 1996).

In 2004 Presidential decree renamed the holiday to “The day of the military parade on the Red Square in Moscow to commemorate the twenty-fourth anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution (1941)” (O vnesenii izmeneniy v statyu 1 FZ № 32..., 2004). However, since 2005 one has been able to observe new shifts in interpretations of November 7. A newly established holiday – the Day of National Unity – is celebrated in Russia now every year on November 4 (see: Russkiye prazdniki...). It is worth noting that the parade itself was held for the first time in 1941. Further celebration was more likely related to the memory of the Great Patriotic War, but not to the revolutionary events. In 2011, there was a reconstruction of the military “parade 1941” on the Red Square, with the Red Army regiments marching directly to the front (Anniversary of Russia’s..., 2014). The date of 1941 emphasized the importance of the holiday according to the speeches of politicians and official statements (Anikin, 2014). However, the parade was put into the context of the battle near Moscow as the beginning of the Nazi invaders’ defeat. Thus, one can observe the substitution of symbols, where the memorial itself becomes the source of commemoration. Notably, position of the authorities is influenced by “overcoming the social-class and political-party approaches practiced in Soviet historiography in assessing the historical significance of the October Revolution” (Kochneva & Fredovna, p. 19), because it may have bad effects (like radicalization and split) on contemporary Russian society.

On the threshold of anniversary, the discourse of revolution’s commemoration was reserved and could be defined as “quiet” without any official celebrations at a high political level and festivities (ibid., p. 20). For instance, the Press Secretary of the President Dmitriy Peskov questioned the need for its celebration (A zachem eto prazdnovat, 2017). Olga Rusakova and Elena Kochneva supposed it is connected with “the policy of neoliberal part, which pursues a course on desovitization as a strategic approach in politics of memory” (Kochneva & Fredovna, p. 20). Although these ideas are not dominant among the members of parliament, these discourse and intentions deeply influenced elite’s mind, “where the source of the negative that was in the Soviet system is the October revolution” (ibid.).

In 2014 President of Russian Federation Vladimir Putin assessed Bolshevik’s actions very critically during the meeting with history teachers and young scholars: “The period of the civil war is a very difficult test for all of our people, good or bad, but the Bolshevik slogans and posters looked brighter, more concise and acted certainly more efficiently. Among other things, it was still fashionable, because no one wanted the continuation of the war; they were in favor of ending the war. It’s true, they cheated the society. Well, of course, you know: “The land is for the peasants, the factories are for the workers, and peace is for the people!” The peace was not given, because the civil war began, the factories and land were taken away, nationalized, so that a scam” (Putin rasskazal ob izyashchnom naduvatelstve..., 2014). Here it is also relevant to pay attention to Putin’s speech to the Federal Assembly in December 2016. It was based on public awareness of the idea of civic concord, reconciliation and national unity: “We need the lessons of history, first of all, for reconciliation, for strengthening the social, political, civil accord that we have been able to achieve today. It is unacceptable to drag splits, anger, resentment and the hardening of the past into our present life, in our own political and other interests to speculate on the tragedies that have touched almost every family in Russia, no matter which side of the barricades our ancestors turned out to be then. Let’s remember: we are one people and we have only one Russia” (Glava RF poprosil..., 2016).

Putin also showed his critical attitude towards Vladimir Lenin and his theory of political management in January 2016 during the meeting of the Council for Science and Education: “It is right to control the flow of thought; it’s only necessary so that this thought would lead to the correct results, and not like in the case of Vladimir Ilyich. Ultimately, this thought led to the collapse of the Soviet Union. [...] There were many thoughts: autonomization and so on. They laid an atomic bomb under the building, which is called Russia, and it jerked afterwards. And we did not need a world revolution” (Putin vyskazalsya o Lenine, 2016). Later in 2017, Putin claimed during the meeting of the Council for the Development of Civil Society and Human Rights that he expects “this date will be perceived by the society as summing up the dramatic events that divided the country and the people” (Sinitsyn, 2017).

Considering all above one can see that the October revolution has different assessment of politicians. From the one hand, Russia does not refuse the relevance of the anniversary for Russian people. On the other hand, the state’s authorities define it in quite an abstract way with predominantly negative attitude to some aspects of the event. Certain beliefs are rooted in “modern phobias of the political establishment, which fear of losing legitimacy and power resources in case of “colour revolution” scenario could be implemented in Russia” (Kochneva & Fredovna, p. 23). Prime minister of Russia Dmitriy Medvedev might prove this idea. He mentioned during plenary meeting of the party “United Russia’s” the forum that Russia “don’t need revolutions at all” as they “have already reached our limit in the last century” (Babushkin, 2016).

Since the elites are likely to ignore references about revolutions in Russia, one can suppose that the authorities are trying to avoid every manifestation of rebellion. To complete the picture, it would be useful to pay attention to citizens’ attitude towards the commemoration of the October revolution.

Commemoration of the event by citizens

Understanding of the revolution events of 1917 has no consensus among academic society. Discussions about this issue led scholars to a solution of considering it to be an aggregate of revolution events taking place in February and October till the beginning of the Civil War (Aleksandr Chubarian – o novom uchebnike istorii..., 2013). According to the research study by Mariya Dontsova and Irina Tazhidinova (2017) for most Russians the scholar’s solution is not appropriate. Their study is based on student survey (held in 2017 among 17 students of physics and technical faculty and 86 – of history and international relations faculty of Kuban State University) with the purpose of revealing the “state of the historical memory of October 1917, the modern public mood about the revolutionary past of the country” (ibid., p. 16). According to the survey, most of students (76%) named Russian Social Democratic Labour Party as the one who had led the revolution. Its head was called in 85% of cases. Dontsova and Tazhidinova argue that a question about the associates of the leader had more problems. However, students’ choice fell on Trotskiy and Stalin. The authors insist on conscious decision making reflecting on like-mindedness, for Trotskiy was mentioned most frequently. The situation is more complex in case of naming the city, where the event began. Majority of physics and technical faculty students chose Moscow (59%) whereas most of history and international relations faculty students (FHIR) – Petrograd (79%). Ideas of revolutionaries, according to FHIR students’ opinion, underlie the works of Karl Marx in 92%. As for students of physics, K. Marx was mentioned only in 65% of cases. Besides they named Emmanuel Kant (18%), Charles Darwin (6%), while 12% was unsure. With regard to the question about separation of October and February events, the survey shows that students did not always do it: most of them were sure the revolution provided to loss of political power by Nicolas II in autumn 1917. Only 45% of FHIR and 24% of physics gave the right answer, having chosen Provisional Government.

It is worth emphasizing that the authors of the research argue that majority of students learned about the revolution from schools (FHIR – 95% and physics – 82%), universities (34% and 18%) or from artwork (film, literature etc.). Media as a source of the information was not favored among young people (12–28%) that “may indicate either lack of coverage by Russian media of country’s revolutionary past or lack of interest among students themselves in such information, even if they are not ignored by the media” (ibid., p. 17). Relatively infrequent source for 30% of FHIR and 15% of physics students were members of the family.

Attitude to the revolutionary events and perception of their connection with the present by today’s youth remains either ambiguous or negative. Students described the definition of revolution as “coup d’etat” or “changes” (“…of the system” or “…of the State structure”). As the research shows these connotations were associated with mentions of fear, threats, uncertainty or anxiety for the people who had witnessed that period of history. This may explain why most respondents were unable to say what consequences of the event had been for the country. On the other hand 33% of FHIR and 41% of physics students considered the revolution to be “an ambitious social experiment” or “a tragedy of Russia” (33% and 12% respectively). Only minority argued for “a boon to Russia”.

Significance of the revolution is estimated as critical (regression) by 42% of FHIR and 29% of students of physics. However, it was evaluated as positive (progress) by 35% of FHIR and 59% of students of physics. It is worth noting that although absolute majority see the anniversary as unnecessary to celebrate, they are unlikely to bury the holiday into oblivion. Hence, despite “predominantly negative perception of the consequences of the revolution for the development of the country” the young people present no categorical attitude (ibid.). Since the role of media attention was partly mentioned in the research study, it is proposed to consider the Russian media discourse in the context of the commemoration of the October revolution.

Media about the Revolution

The topic of the October Revolution did not find popularity with the national media. According to the report of the “Center for Russian Political Culture Studies” (Spustya sto let..., 2017) mentions about the revolution in federal media were growing slowly until 2016 (see Pic.1). The sharp increase in media attention to the topic was noticeable from the third quarter of 2016.

Picture 1. The mention of the October revolution in the federal media in 2007–2017.

Source: Center for Russian Political Culture Studies

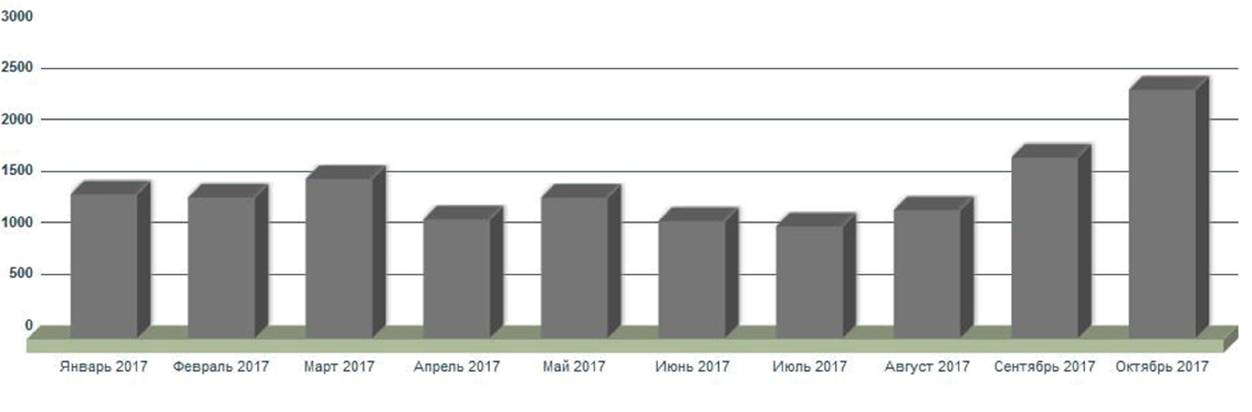

The greatest number of publications about the oncoming anniversary appeared in 2017. However, the numbers varied each month and mentions regarding the topic were slowly gaining momentum until October (see Pic. 2).

Picture 2. The mention of the October revolution in the federal media in January–October 2017.

Source: Center for Russian Political Culture Studies

The picture shows that there were 1,240 federal publications during regional elections in August. It was 10–15 percent more than in the previous few months. From September media attention to the commemoration topic increased markedly (and even twice in October). Notwithstanding, a sociological survey in October (based on opinion of 1500 respondents from different regions) noted the trend in low level of public attention to the anniversary of the revolution, for three-fifths of respondents (58 percent) consider that the issue did not have proper media coverage (ibid.). Less than a third of Russians (29 percent) stated they had known or had heard about preparations for the anniversary event. Part of respondents, who were not interested in this topic, was approximately 3 percent. Moreover, the authors of the report point out a correlation between an age cohort and awareness of the event. The level of interest was the lowest among young people aged 25 to 29, whereas it was one third below average in the age group forty and under. The highest rate recorded in the 45–49 and 65–69 age range. The authors further noted that supporters of opposition parties had much higher awareness of the topic than electorate of the ruling party (“United Russia”) or those who vote “against all” or abstain.

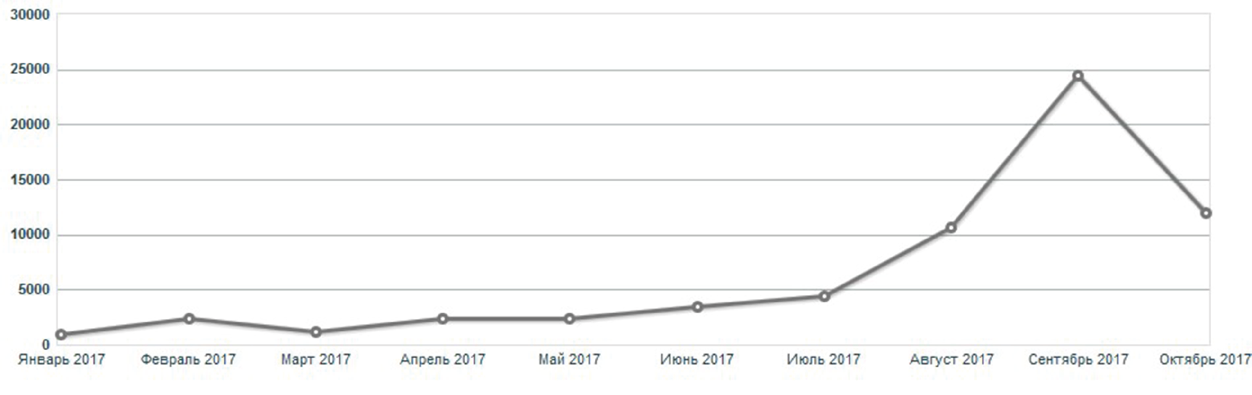

According to these figures, it turns out that public attention was not focused on the anniversary of the revolution. This raises the question of what topics dominated the internal media discourse. TV coverage tended to broadcast traditional foreign policy topics including situation in Ukraine, crisis in relations with the West and war in Syria. However, there were shifts in emphasis towards “the scandal around a major failure of the state cultural policy” (ibid.). The film Matilda (Uchitel, 2017), dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the October Revolution, was accused of utilizing political campaigning. Instead of proposing deliberation of the cause and historical consequences of the revolution, the vector of public attention was directed to the movie about the romantic relationship between Nikolay Romanov and the ballerina Matilda Kshesinskaya (Spustya sto let..., 2017). According to the report, the number of references to the October revolution and Matilda was comparable in the beginning of 2017. However, the number of publications about the movie increased rapidly in August (see Pic. 3).

Picture 3. Mentions of the scandal around the film Matilda in federal media in January–October 2017.

Source: Center for Russian Political Culture Studies

There were ten times fewer mentions about the October revolution than about Matilda in media in September 2017. A similar trend was also observed in social networks: public attention to the film decreased, while the interest in the revolution increased. Despite the different dynamics, the number of references to the movie was “more than five times higher than to the October revolution”. Nevertheless, the media attention was diminishing by the time of the official premiere of the film (October 23). Subsequently, the topic was replaced by the news of the nomination of new presidential candidate in the person of Kseniya Sobchak (ibid.).

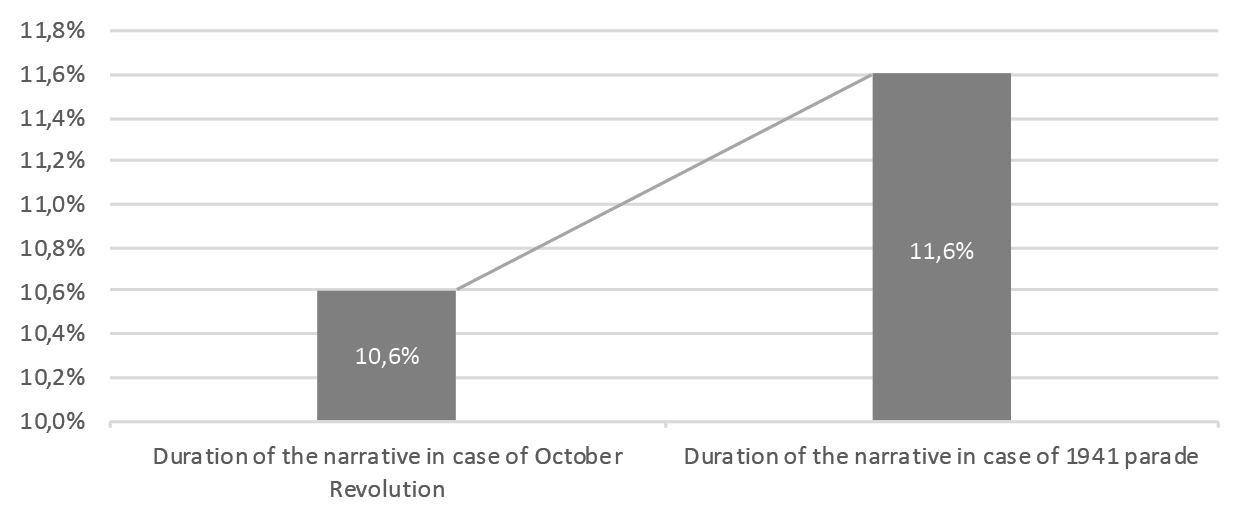

No less interesting is media attention on the day of the celebration the anniversary of the October Revolution (November 7, 2017). Since television remains the main source of information in Russia by different estimations (Kanaly informatsii, 2018; Doveryay..., 2017), it is proposed to consider the narratives appeared in the evening news program “Vremya” on the main Federal channel “Pervyy kanal”. The program showed the news mostly about external policy (e.g. Syria, Ukraine, Vietnam or USA) and/or situation in the world. The Picture 4 presents the share of narratives about both the Revolution and the 1941 parade during the news program’s broadcasting.

Picture 4. Share of the selected narratives on TV program “Vremya”

Source: own elaboration

The entire duration of “Vremya” program on November 7 was about 29 minutes. However, the information about the events demonstrated a low media attention (10–11% or about 3 minutes in average). It may confirm the assumption mentioned previously that the anniversary itself was not relevant for most elites. Communist Party of Russian Federation was the only authority cited by the media: “in honor of 100 years of the October Revolution, the representatives of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation organized a march in the center of Moscow” (“Vremya”, November 7). The leader of the party Gennady Zyuganov claimed that “Aurora’s shot gave all the inhabitants of the planet the point of Marxism-Leninism and the great idea of freedom and happiness that every worker on earth deserves. Any lie, dirt and intrigue trying to silence the great October and turn over his immortal conquests are unworthy of our attention”. The revolution was described as “the main event of the year, if not decades” or “100 years ago here in the center were the bloody battles of the Bolsheviks” (“Vremya”, November 7). Foreign delegations were mentioned once as “guests from 80 countries”, including those who are from Brazil, Catalonia and Greece.

1941 parade was considered to be a solemn commemoration. The presenter and the journalist described it as “a solemn parade in Moscow in memory of the legendary parade of 1941, whose participants went to defend the capital from the Red Square”, “on the square, grandsons and great-grandchildren of the winners, who left to the front in the autumn of 1941 from the walls of the Kremlin”, “march of holy war” (“Vremya”, November 7). In comparison with the October revolution, parade the 1941 parade was presented as much more significant and positive issue. It is worth noticing that Putin or any other politicians from the government (except left-wing party) have never been mentioned during the narrative about both the Revolution and 1941 parade. Hence, it confirms once again how indifferent the authorities are towards some sites of collective soviet memory.

Conclusions

Analysis of the official Russian discourse of politics of memory regarding the commemoration of the October revolution showed some results. Russian elites have an ambiguous approach to this historical phenomenon. Contradiction between the historical significance of the October revolution and negative reflection of the authorities towards any revolutions in general. Moreover, they did not manage to offer the society a good definition of contemporary understanding of the issue. “The ‘reconciliation strategy’ has come into conflict with the official negative assessments of the practice of Soviet state-building” (Kochneva & Fredovna, p. 26). Commemoration of the event becomes an instrument for political manipulations in terms of the way of interpretations that are appropriate for the officials. For instance, policy of desovietization was implemented in post-soviet period with the discourse of persuasions that the October revolution contributed to criminal and totalitarian nature of the Soviet regime.

The research study by Mariya Dontsova and Irina Tazhidinova shows that majority of young people see the anniversary as unnecessary to celebrate. However, respondents state that the holiday should not be buried into oblivion. According to the researchers, there is no categorical attitude towards the anniversary, even though the students show “predominantly negative perception of the consequences of the revolution for the development of the country”. Furthermore, public enquiry shows lack of proper media coverage of preparations for the anniversary of the October Revolution. As an alternative, there were only ‘necessary’ images of official position of elites. Media discourse took the form of silence towards the anniversary or substitution for related topics as distracting campaigns, instead of proposing deliberation of the results, lessons and modern heritage of the October revolution.

Additional info

The paper was written due to the support of “Program Mentoringowy Forum Młodych Medioznawców i Komunikologów Polskiego Towarzystwa Komunikacji Społecznej”.

References

O vnesenii izmeneniy v statyu 1 FZ № 32. O dnyakh voinskoy slavy (pobednykh dnyakh) Rossii. Retrieved from: http://base.garant.ru/12138252 (September 2018).

Spustya sto let. Nezabytaya revolyutsiya. Otnosheniye rossiyan k Oktyabrskoy revolyutsii. eye deyatelyam i dostizheniyam. Analiticheskiy doklad. (2017, November 3). Tsentr issledovaniy politicheskoy kultury Rossii. Retrieved from: http://cipkr.ru/2017/11/03/spustya-sto-let-nezabytaya-revolyutsiya-otnoshenie-rossiyan-k-oktyabrskoj-revolyutsii-ee-deyatelyam-i-dostizheniyam-analiticheskij-doklad/ (July 2019).

A zachem eto prazdnovat? Peskov o stoletii Oktyabrskoy revolyutsii. (2017, October 25). Retrieved from: https://newsland.com/user/4297826898/content/a-zachem-eto-prazdnovatpeskov-o-100-letii-oktiabrskoi-revoliutsii/6051513 (July 2019).

Aleksandr Chubarian – o novom uchebnike istorii: Samaya slozhnaya problema. s kotoroy my stolknulis. – Sovetskoye obshchestvo. (2013, October 30). Retrieved from: http://www.nakanune.ru/articles/18265 (July 2019).

Anikin, D. (2014). Simvolicheskaya borba s sovetskim proshlym: parad v kontekste politiki pamyati. Vlast. № 2, pp. 139–142. Retrieved from: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/simvolicheskaya-borba-s-sovetskim-proshlym-parad-v-kontekste-politiki-pamyati (July 2019).

Anniversary of Russia’s October Revolution in Facts. (2014, November 7). Retrieved from: https://sputniknews.com/russia/201411071014492334/ (July 2019).

Babushkin, K. (2016. June 21). Dmitriy Medvedev vystupil s programmnym zayavleniyem na Forume «Edinoy Rossii» v Magnitke. Retrieved from: https://www.znak.com/2016–06–21/dmitriy_medvedev_vystupil_s_programmnym_zayavleniem_na_forume_edinoy_rossii_v_magnitke (July 2019).

Bałdys, P., Piątek, K. (2016). Memory politicized. Polish media and politics of memory – case studies. Media i społeczeństwo. 6, 64–77.

Carrier, P. (Spring 1996). Historical Traces of the Present: The Uses of Commemoration. Historical Reflections/Réflexions Historiques. 22(2), 431–445.

Dontsova, M.V., Tazhidinova, I.G. (2017). Oktyabrskaya revolyutsiya 1917 goda v istoricheskom soznanii sovremennoy studencheskoy molodezhi. Naslediye vekov. 2, 15–19.

Efremova, V.N., Malinova, O.Yu. (2018). Kommemoratsii istoricheskikh sobytiy i gosudarstvennyye prazdniki kak instrumenty simvolicheskoy politiki. In: V.A. Tishkov. E.A. Pivnevoy (eds.). Istoricheskaya pamyat i rossiyskaya identichnost. M.: RAN.

Ensink, T., Sauer, C. (eds.). (2003). The Art of Commemoration: Fifty years after the Warsaw Uprising . Amsterdam: Ebsco Publishing.

Federalnyy zakon ot 13.03.1995 N 32-FZ. O dnyakh voinskoy slavy i pamyatnykh datakh Rossii. Retrieved from: http://consultant.ru/document/cons_doc_LAW_5978/247d10b68af90f6af20e0682d454c46231efc7d9/ (September 2018).

Glava RF poprosil ne spekulirovat na tragicheskikh stranitsakh istorii 2016. (2016, December 1). Retrieved from: https://www.interfax.ru/russia/539416 (July 2019).

Irwin-Zarecka, I. (1994). Frames of Remembrance. The Dynamics of Collective Memory. New Brunswick etc.: Transaction Pub.

Kochneva, E., Fredovna, O., (2017)Otsenki Oktyabrskoy revolyutsii v ofitsialnom diskurse politiki pamyati. Diskurs Pi. UrO RAN.

Levada-Center. (2018). Kanaly informatsii. Retrieved from: https://www.levada.ru/2018/09/13/kanaly-informatsii/ (July 2019).

Narskiy, I. (2017. October 30). Sto let prevrashcheniy russkoy revolyutsii. Istoricheskiye Issledovaniya. 6. Retrieved from: http://www.historystudies.msu.ru/ojs2/index.php/ISIS/article/view/109/293 (September 2018).

Putin rasskazal ob izyashchnom naduvatelstve bolshevikov. (2014, November 5). Retrieved from: https://lenta.ru/news/2014/11/05/bolsheviki/ (July 2019).

Putin vyskazalsya o Lenine. (2016, January 21). Retrieved from: https://regnum.ru/news/polit/2060692.html

Russkiye prazdniki kak otrazheniye dukha naroda. Retrieved from: http://www.km.ru/front-projects/russkie-prazdniki-kak-otrazhenie-dukha-naroda/7-noyabrya-datatrebuyushchaya-pereosmy (July 2019).

Saprykina, M. i G. (2016). Oktyabrskaya revolyutsiya 1917 g. kak faktor sotsialno-politicheskoy identifikatsii na postsovetskom prostranstve: postanovka problemy. Nauka. Mysl: elektronnyy periodicheskiy zhurnal. 8(1), 63–67. Retrieved from: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/oktyabrskaya-revolyutsiya-1917-g-kak-faktor-sotsialno-politicheskoy-identifikatsii-na-postsovetskom-prostranstve-postanovka-problemy (July 2019).

Sinitsyn, V. (2017. October 30). Data stoletiya Oktyabrskoy revolyutsii stanet podvedeniyem cherty i simvolom vzaimnogo proshcheniya – Putin. Retrieved from: https://tvzvezda.ru/news/vstrane_i_mire/content/201710301629-o6ey.htm (July 2019).

Uchitel, A., Dostman, A., Vinokur, V., Korotkov, V. (Producers). Uchitel, A. (Director). (2017). Matilda. Rossiyskaya Federatsiya: TPO Rok.

Ukaz Prezidenta RF ot 07.11.1996 № 1537. O dne soglasiya i primireniya. Retrieved from: http://legalacts.ru/doc/ukaz-prezidenta-rf-ot-07111996-n-1537/ (July 2019).

Vypusk programmy „Vremya” v 21:00. 7 noyabrya 2017 goda. (2017, November 7). Retrieved from: https://www.1tv.ru/news/issue/2017–11–07/21:00# (July 2019).

WCIOM. (2017). Doveryay. no proveryay! Ili ob osobennostyakh sovremennogo mediapotrebleniya v Rossii. Retrieved from: https://wciom.ru/fileadmin/file/reports_conferences/2017/2017–10–26_smi_abr.pdf (July 2019).

1 The first date is based on the Julian calendar, whereas the second – on the Gregorian one.