Creating Putin’s Victory. Analysis of the Russian President’s Image in the Light of Russian Media Coverage of the 2018 Russia–United States Summit in „Время” News Program

Tworzenie zwycięstwa Putina. Analiza wizerunku Prezydenta Rosji w rosyjskich mediach na przykładzie relacji ze szczytu Rosja-Stany Zjednoczone w 2018 roku w programie informacyjnym „Время”

Abstrakt

Takie wydarzenie, jak Szczyt USA–Rosja w Helsinkach (2018 r.), nie mogło zostać zignorowane przez media. Jego program szybko rozprzestrzenił się w całym świecie, przyciągając uwagę różnych zaangażowanych stron. Skoro informacje są obecnie uważane za miarę wartości wydarzenia, istotne jest nawet nie tyle, o czym dyskutowali przywódcy polityczni, co w jaki sposób zostało to przedstawione w mediach. Na Zachodzie Szczyt może być postrzegany jako względne zwycięstwo Putina, a jednocześnie jako porażka Trumpa. Jednak ujmując tę kwestię w kontekście wojny informacyjnej skierowanej przeciwko własnym obywatelom, której celem w tym przypadku jest manipulacja nastrojami społecznymi i kształtowanie (korzystnego) wizerunku lidera kraju, należy stwierdzić, że negocjacje te były więcej niż udane dla Federacji Rosyjskiej.

Abstract

Such a resounding issue like US–Russian Summit in Helsinki (2018) could not be ignored by any media coverage. Agenda was rapidly spread all over the world, hence attracted attention of different actors. Since nowadays information is considered to be a measure of value, it is relevant even not as much what the political leaders discussed as how the media framed that agenda. Even from the standpoint of Western studies of the Summit it might be perceived as a relative victory for Putin and at the same time a relative loss for Trump. However, addressing this issue under the context of information warfare directed at its own citizens, the aims of which, in this case, are manipulations of population’s moods and establishment of a (favorable) image of the leader of the country, the negotiations were more than successful for Russian Federation.

Keywords

- information warfare, Rosja, Russia, Stany Zjednoczone, Szczyt USA-Rosja w Helsinkach, The United States, US-Russia summit in Helsinki, wojna informacyjna

Introduction

Total control over the content of information has been perpetrating since Vladimir Putin took power. Hence, information warfare of Russian Federation is directed not only at international audience, but also at its own citizens, where Russian media are trying to give a ready picture of the ‘correct’, according to the Kremlin, perception of the world. Such a resounding issue like the US-Russian Summit in Helsinki (2018) should have served as another reason for Putin’s aim to prove that Russia is an equal actor in the international arena and show it to the people in his country.

The Helsinki summit was considered to be one of the most highly anticipated events of July. It was first formal meeting of Russian President Vladimir Putin and American President Donald Trump and could not have been ignored by any media coverage all over the world. On the eve of the Summit visits of President Trump were undertaken to a number of EU countries, including Belgium where the NATO summit in Brussels was held. D. Trump “quickly struck a confrontational tone with allies” (Polyakova, 2018), criticizing them for small payments for collective defense and calling “Germany ‘a captive to Russia’ over the Baltic Sea pipeline project” (Mikelionis, 2018). Thus, European Union was worried about possible effects of the presidential negotiations. No agenda was officially announced for their discussion, and no communique was signed afterward. It the press conference following the Summit Putin and Trump told about some issues what were discussed: Syrian civil war in the context of efforts to combat terrorism and limitations of Iranian troops near Israel-Syria border for the safety of Israel (Wintour, 2018); cooperation in Syria in form of humanitarian aid by way of reconstruction of the state and facilitation of the repatriation of Syrian refugees (DeYoung , 2018); economic relations about status of sanctions did not have a broad discussion, however, the only greatest barrier to sanctions being lifted remains Ukraine and Crimea issues on which both presidents have an opposite point of view (Wintour, 2018); nuclear talks about extension of the Start treaty that expires in 2021 and review of the Intermediate Nuclear Treaty that eliminated all nuclear and conventional missiles and their launchers of intermediate range of 500–5,000 km (Wintour, 2018); energy task related to a gas pipeline ‘Nord Stream 2’ from Russian Federation (RF) via the Baltic sea into Germany won’t omit gas transmission through Ukraine in case of settlement of disputes between Russia’s Gazprom and Ukraine’s Naftogaz in the Stockholm arbitration court (Wintour, 2018). There were also plenty of questions concerned Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections. V. Putin denied that RF is linked to any interference, and D. Trump stated he had confidence in both parties: United States Intelligence Community insisting on Russian involvement and Putin’s negation (“Transcript: Trump And Putin’s Joint Press Conference”, 2018). After the Summit was over President Trump has been criticized by the media in the United States (one see Fox News, Business Insider, CBS News, ABC News, and CNN ) and in the European countries media reaction were mostly negative towards D. Trump (one can follow, for example: Bild, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Spiegel (Germany); The Mirror, The Sun, The Guardian, The Times (UK); Le Monde (France).

Although agenda of the US-Russian Summit in Helsinki became popular worldwide often in the form of a relative victory for Putin and a concurrent relative loss for Trump, notwithstanding, there is a lack of academic research of the event so far. It is therefore proposed to consider the issue from the perspective of communication science and media studies. Moreover, this paper calls for the overview of the Summit and President Putin issues through the prism of domestic level of information warfare, the aims of which, in this case, are manipulations of population’s moods and establishment of a (favorable) image of the leader of the country and to show that the negotiations were more than successful for Russian Federation. The purpose of the article is to focus on the Helsinki 2018 agenda and how Russian media framed the US-Russia Summit and the medial image of Putin for Russians in the context of the meeting on the example of the ‘Time’ (‘Время’) program on the ‘Channel One’ (‘Первый канал’). First of all it is necessary to operationalize and implement what is understood by the term agenda and information warfare.

Agenda-setting

Agenda-setting describes the ability of the media to define what issues become the focuses of public attention. For the first time the theory appeared in Walter Lippmann’s 1922 book “Public Opinion”. Although the author does not use the term ‘agenda-setting’, he argues that the media is tend to be a link between the real world and a pseudo-environment, hence, plays a key role in making pictures in people’s heads (Lippmann, 1922). Following his idea Bernard Cohen mentioned in his work “The press and foreign policy” (1963) that the theory of agenda-setting is not only the matter of topic, as the press “may not be successful much of the time in telling people what to think, but it is stunningly successful in telling its readers what to think about. The world will look different to different people” (Cohen, 1963). Later Maxwell McCombs and Donald Shaw, basing in Cohen and Lippmann’s thoughts, found a correlation between what election events people considered to be most relevant and what the media presented while presidential election campaign in the United States in 1968 (Kazun, 2017). Their work was the very first empirical study on the impact of agenda-setting, where they focused on comparing the issues on the media agenda with relevant issues on hesitant voters (Kazun, 2017). What they managed to prove was that media had influences on public opinion by inducing undecided voters to concentrate their attention on certain issue, ignoring the others. Thus, that provided to understanding of the topic’s hierarchy process classified in order of importance. This evidence served as an empirical application of further studies on the examples of the Gulf War, the Watergate scandal, environmental pollution, and even organ donation (Iyengar & Simon, 1993; Weaver, McCombs & Spellman, 1975; Ader, 1995; Feeley, O’Mally & Covert, 2016).

Agenda-setting theory refers to formation of public awareness and concern of salient issues by the news media. Most researches are dedicated to two basic assumptions: “the press and the media do not reflect reality; they filter and shape it; media concentration on a few issues and subjects leads the public to perceive those issues as more important than other issues” (Freeland, 2012). It is worth bearing in mind that the time frame and different potential of media diversity are also pivotal aspects for the agenda-setting role in mass communication (Freeland, 2012).

According to Everett M. Rogers and James W. Dearing the following types of agenda are distinguished in particular: public, media and policy agenda-setting (Rogers & Dearing, 1988). Public agenda refers to public determination of which issue is newsworthy, and media agenda indicates the impact of the mass media on the audience. Policy agenda represents the influences both public and media agenda on the decisions of public policy makers (Walgrave & Van Aelst, 2006). Since this article is supposed to consider the media agenda-setting, it is pertinent to mention that the effect of the media on people’s perceptions of the significance of the issue may be different. In accordance with the audience effects model “the media’s coverage of events and issues interact with the audience’s pre-existing sensitivities to produce changes in issues concerns” (Freeland, 2012, p. 5). This might suppose that the existence or absence of a personal experience implies a person’s predisposition to be most or less affected by the issue of high relevance. Here one can see the importance of obtrusive or unobtrusive issues. Obtrusive matters pertain to common topics that affect nearly everyone (e.g. high gas prices, increased costs of food products), but based rather on a personal experience of the individual. Research suggests that media agenda of the unemployment rate might not have any influence on those in a stable job as much as those recently unemployed (Walgrave & Van Aelst, 2006). Unobtrusive topics may be expressed in terms of more distant questions to the public (e.g. a political scandal, summit NATO or the meeting of the presidents of Russia and the US in Helsinki) (Walgrave & Van Aelst, 2006).

It is relevant to put emphasis here on one of the important determinants of the agenda-setting research paradigm that will be taken into account in the empirical part of the article. Agenda influence may also be defined through the prism of how an issue or an event is explained by the media coverage and interpreted by the audience. Theory of framing, that can be both a part of agenda-setting theory as an addition to public perceptions of issue importance (Price & Tewksbury, 1997) and also a separate phenomenon as shifts in attentiveness to sub-issues (McCombs, Shaw & Weaver, 1997), “is said to occur when, in the of describing an issue or event, a speaker’s emphasis on a subset of potentially relevant considerations causes individuals to focus on these considerations when constructing their opinions” (Druckman, 2001, p. 1042). Selective exposure of information to an audience in the form of particular attributes for the news media agenda causes the impact of how this information will be understood. The purpose for framing narratives is to shape a storyline around a series of events (Gamson & Modigliani, 1987) and define or incline the public to how to evaluate the information being given to them in an expected way (McQuail, 1994). This approach may show changes in public opinions caused by the information received from the media “promoting a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation” (Entman, 1993). It is worth paying attention to that frames may be characterized by omitting or obscuring and including certain information and either in conscious or unconscious way by the media (Gamson, 1989).

Since television is considered to be the most primary source of information for 73% of Russians, with the exception of the youngest respondents (aged 18 to 24 years) – 49% (Levada-Center, 2018), it is worth noticing about Georg Gerbner’s cultivation theory. It is based on the assumption of a passive role of the recipient, where the world view perception creating by heavy viewers is a reflection of the media narratives (Gerbner, Gross, Jackson-Beeck, Jeffries-Fox & Signorielli, 1978). The main reason for this is that “the more time people spend ‘living’ in the television world, the more likely they are to believe social reality aligns with reality portrayed on television” (Riddle, 2009). Thus, as a result of cultivation, people shape misperceptions about the world. The author states that the effects might influence the audience only after a long, cumulative television exposure (Cohen & Weimann, 2000). Put differently, this theory may reflect the impact of TV on perception of the reality by individuals based on the amount of time a person devotes to TV watching. It also depends on the quantity of repetitive and emphasized images and issues presented on television (Gerbner, Gross, Morgan & Signorielli, 1994). In this perspective cultivation theory might be useful in assessment of the phenomenon of the correlation between a certain approach to the subject (often with a negative attitude, e.g. Western countries are hostile to Russia) and the consignee’s perception of this topic as credible in the Russian media.

In the context of media influences on the perception of political events, where it is the only channel of the political agenda, it is likely to take a look at the issue of freedom of speech. Since media and elites may form public debate it stands to reason that they are able to shape free speech: there can be both restrictions on specified actors and media selection and framing the necessary news (Wojtkowski, 2010). Thus, the key question would be whether agenda-setting process can be considered to be some form of censorship. Darren O’Byrne may give a good point on that: “In human rights circles, censorship is treated as an affront to individual freedom, a violation of our rights to know, to think, to express ourselves. It is a tool for state repression, for the maintance of power (the task of any state, whatever colour its rosette may be and whatever it claims for itself), achieved through the manipulation of the cultural sphere – ‘the history of censorship belongs to the history of culture and communication’…” (O’Byrne, 2003, p. 116). It can be assumed that despite censorship in itself may be an obstacle to freedom of speech, it can contribute to creating agenda-setting process. That may reflect a voluntary censorship relating to the situation, when an individual or an organization basing on common beliefs lays down upon others restraints not legally binding on what they should (not) say (O’Byrne, 2003). That also may concern a subterranean censorship, which is defined as abusing one’s power unrelated to impose censorship without direct government involvement (O’Byrne, 2003). Due to the account that mass media tend to select, prime and frame media coverage of an issue may cause limitations on the access to media reality as over 99% of events worldwide are usually ignored (Wojtkowski, 2010). Therefore in mediatization process the media play role of the Fourth Estate that imposes political communicators and public opinion to respond to the media’s rules (Wojtkowski, 2010). On the other hand, also a legal censorship has an important influence on how agenda-setting process is working in a particular state. In case of Russian Federation it is necessary to mention that the monopolization of state-owned media prevails on the market. This can cause pressures on independent mass media in the country from government what is especially true of television at the national level.

Information warfare as a non-military dimension of “hybrid wars”

In this section it is necessary to consider why it is important to pay attention to the relationship between the media and the government, which create effects on the domestic level of media coverage. Here the theory regards the aspect of interpretations of events by the media through the lens of the term of information warfare, which is nowadays also used as an integral part for military purposes.

Studies on international security provide different perspectives on understanding hybridization of waging wars. It is relevant to emphasize that the concept has no universal definition among theoreticians and practitioners of military thought, hence it is quite challenging to apply a certain approach. Particularly noteworthy is the fact either that military combination (or hybridization) is nothing new in terms of various scientific disciplines regarding wars: a similar combination of different elements was observed in many wars of the past (Skoneczny, 2015; Sun Tzu; Пухов, 2015). Notwithstanding, the hybrid war as a concept appeared for the first time at the beginning of the 21st century, mainly in American literature. Based on previous studies, which included such terminology as e.g. asymmetric war, proxy war, low intensity conflict, fourth generation war (Deutsch, 1964; Mumford, 2013; Lind, Nightengale, Schmitt, Sutton & Wilson, 1989; Sarkesian, 1985), the nature of the “hybrid” takes the form of various methods and features of combat, weapons, aimed at achieving the defined military effect. William J. Nemeth, studying Russian-Chechen war, describes elements of ‘hybridity’ and characterized the concept as a conflict containing unusual organization of the army (its decentralization), blurring the border between the military and civilians, atypical ways of using military forces (e.g. guerrilla operations), adaptation of “not only tactics, but also technology to their needs” (e.g. telecommunications), using effective psychological and information operations (Nemeth, 2002, pp. 49–63). Frank G. Hoffman, developing Nemeth’s idea, stated that hybrid war would be “complex” (a combination of conventional and irregular activities at the strategic, tactical and operational level) and “unlimited” (multi-directional, synchronous and asymmetric) (Hoffman, 2007, pp. 18–25). Hybrid conflict also should include conventional and irregular tactics, armed groups, terrorism and crime; state and non-state actors; combination of modern technologies and guerrilla warfare (Hoffman, 2007). Their proposals indicate using more advanced instruments (guerrilla and technologies) in modern conflicts unlike the previous studies of their predecessors (Cohen, 1997; Gates, 2010; Mack, 1975), who were mainly focused on US areas of interest, asymmetrical and terrorist threats as advantages of small nations over big, excluding the probability of implementing a similar scenario by a more powerful actor.

As far as major focus of this article relates to Russian Federation it is worth to pay attention to a vision of Russian General Valery Gerasimov, who epitomizes strategies of military and non-military actions of the state. In his report ‘The Value of Science Is in the Foresight’ (Герасимов, 2013) he didn’t mention the term of ‘hybrid war’, however, described how such conflicts might look like in the future. V. Gerasimov mostly alluded to blurring the lines between the states of war and peace, inasmuch as there is no declaration of war as such, what one could see in the case of Ukraine. Something more interesting one can see in his particular attention to “the broad use of political, economic, informational, humanitarian, and other nonmilitary measures, – applied in coordination with the protest potential of the population, – […] which are supplemented by military means of a concealed character, including carrying out actions of informational conflict and the actions of special operations forces” (Герасимов, 2013). He also focused on asymmetrical actions, which allow a state to “use of special operations forces and internal opposition to create a permanently operating front through the entire territory of the enemy state, as well as informational actions, devices, and means that are constantly being perfected” (Герасимов, 2013). According to his report, the priority will be to strive to weaken the opponent and his state structures and to coerce him into the assailant’s will. Summa summarum Gerasimov assumed that “the role of nonmilitary means of achieving political and strategic goals has grown, and, in many cases, they have exceeded the power of force of weapons in their effectiveness” (Герасимов, 2013). This statement is confirmed, for example, by Russian scholar Andrey Manoilo. He maintains in his article ‘Hybrid Wars and Color Revolutions in World Politics’ that “in the hybrid war information operations (information warfare operations) can be crucial for compelling an enemy to capitulation, and military operations can play a service role, providing information warfare organizers with the PR material, which is necessary for information attacks on the consciousness and subconscious of the enemy for the purpose of inflicting direct damage (by information weapons) and covert control over his consciousness and behavior” (Манойло, 2015). As it is briefly presented RF relies more on non-military strategies since they are more effective and achieve results for a very short time. An example is the swiftness of information operations directed against, for example, Finland (where the Russians are threatened by NATO, and the Finns do not want to spoil relations with the Russian Federation on this basis (“Get ready for pro-Kremlin tinnitus”, 2017) or Ukraine (the Crimeans as an example of information warfare at the international level and Russians – at the domestic one (“Someone Said That the Referendum in Crimea was Legitimate”, 2018).

Here it is essential to consider the term of information warfare (IW) in greater detail and how it relates to manipulations of public opinion, including own citizens of a state. Non-military actions represent a set of influences on consciousness and subconsciousness that are expressed in the face of manipulation of information. It is worth noting that, like the term of hybrid war, there is no unambiguous definition of IW’s concept and it combines different elements and strategies. Therefore, based on the objectives of this article, the information warfare will be considered through the lens of a neglected aspect in the literature.

Jans Berzins tried to describe IW – on the example of processes in Ukraine – through the prism of psychological warfare (PW), where the main battlefield is the mind. It is worth emphasizing that he came close to understanding of strategical thought of Russian Federation. It uses means of influencing the environment (not) favoring its invasion of Ukraine, methods of intimidation, corruption, bribery, propaganda and disinformation in the media and the Internet for dysfunctional purposes (Berzins, 2014). The main goal of this strategy is to gain control over the mood of the armed forces and the civilian population of the enemy. Despite this theory relates more to foreign policy PW could also be used on the domestic level as citizens might be a destructive element for the government and the state in both cases.

It is also worth recalling that IW may be understand through disinformation or providing information in a beneficial way for a consignor, used by individuals, states and non-state actors (Gronowska-Starzeńska, 2017). The effects might be different: demoralization of the other party or distortion of the events’ assessment. Reliable information is based on accurate or approximate information retrieval. That means that the first message should be the source of the information and the secondary message is the result of processing the first one. A distortion takes place in case there are any distinctions. Different actors including mass media may use this approach so that to influence the audience quicker, to create a specific message, which might be a key issue in public opinion, and at the same time they can distract the audience from important things by focusing on the area of less important and controversial topics (Wrzosek, 2012).

Although Russia provides its information operations also towards international arena, where an information flow in global sense touches various audiences and where Russia tries to find an individual approach for each country, here it is worth paying attention to the significance of domestic level of IW directing on the state’s own citizens, who must be sure that the actions of the state and its leaders are correct, so that the Russian Federation can minimize anti-government movements in the country and focus on foreign policy interests. With this understanding the abovementioned aspect can be interpreted as close to a concept of internal propaganda and manipulations and psychological operations (Wrzosek, 2015). Different actors like “independent Russian journalists and human rights defenders are systematically misrepresented as agents of foreign governments, as are opposition politicians and environmental activists” (“Russia as a Target of Russian Disinformation”, 2018). Indeed, Russian media system is professionally developed, and meanwhile, it is highly monopolized by the state. Hence, the media market may be considered to be totally under control by the government with single exceptions of partly free media (e.g. Radio ‘Echo of Moscow’, ‘Dozhd’ TV channel). Russian people receive a ready picture of the “correct” perception of the world, where the enemy is pointed in the form of the West determined to hatred for RF (Darczewska, 2015). It is worth bearing in mind that the key actor influencing the direction of politics and creating a certain image of the Russian Federation inside the country (and beyond its borders as well) is Russian President Vladimir Putin. His party itself – a tough, authoritative and uncompromising leader who lifted Russia from his knees and can lead the state to the number of the most developed countries – is a subject of study of many researches (Russian Analytical Digest, 2013; Simons, 2016; Lipman, 2009; Полозов, 2018; Vinogradova & Denisova, 2018). However, here it is worth paying attention to the lack of publications on the aspect of the President’s image in the Russian media at domestic level and in the context of information warfare that has been the main purpose of this article.

Methodology of the study and research hypothesis

Methodologically, the research was based on content analysis of the Russian media coverage of the US–Russian Summit in Helsinki agenda in the ‘Time’ (‘Время’) program on the ‘Channel one’ (‘Первый канал’) from June, 27 till July, 22 (for more information see the appendix). Since television is considered to be the most primary source of information for 73% population (“Каналы информации”, 2018), it was decided to select one the most popular TV channel in Russia. The ‘Channel one’ was chosen according to the survey of the news resources’ popularity, where percentage of viewers is 72% (Информационные источники, 2018), hence, where ‘Time’ is the top-ranked news program. The target dates were not random: June 27–July 15 and July 17–July 22 are the period of the Summit agenda genesis and terminus, respectively; July 16 is the very day of Putin’s and Trump’s meeting.

Around 26 editions of the ‘Time’ were analyzed and the data was coded and assessed in accordance with the needs of categorizing the answers. The selection criteria for inclusion in the sample were based on the subject principle: the Summit mention and the presence of Putin (category 1: Image of Putin) with reference to two other categories in form of methods of manipulations were used to promote Putin and their source. The selected episodes were processed using the method of content analysis of a subject in mass media. The main focus of the research remained on manipulation tools and the interpretation of these features to determine the authors’ intentions by analyzing the data. Possible methods of manipulations were chosen are:

1.Language (Szalkiewicz, 2014, pp. 41–42; Borecki, 1987, p. 128):

- Attaching epithets – use of epithets to discredit the opponent or its ideas, plans.

- Invoking the authorities – use of the authority or support of a well-known person for the intended purpose.

- Bandwagon effect – the situation when a person does something primarily for the reason that others are doing it, regardless of one’s own beliefs.

- Card stacking – use of the right selected and interpreted facts to achieve an intended purpose.

- The method of creating ‘political myths’ – cumulating of certain slogans, concepts or evaluations that create a ‘political formula’ about an issue to induce a necessary response.

- Semantic convergence method – interaction of the previous and next news in terms of contents and or supplements.

2.Psychological

- Halo effect – cognitive bias that means an initial assessment about an object which influences one’s feeling about a person’s character. It can be either positive or negative (Lachman, Sheldon & Bass, 1985).

- Framing effect – cognitive bias which induce people to be inclined to a particular choice by presenting a certain point depending on how it is presented (Plous, 1993).

- Self-serving bias – behavioral interpretation: an individual tends to attribute positive results to himself, but ascribe negative to external factors (Campbell, Keith, Sedikides & Constantine, 1999).

- Assertion – information given as a fact without requiring any explanation.

- Dramatization – creating a sense of anxiety, danger, fear, hysteria, or, conversely, feelings of euphoria or pride.

Drawing on theoretical framework of the related literature the main purpose of this article was founded on the following assumptions:

Hypothesis 1: The US-Russian Summit in Helsinki (2018) should have served as another reason for Putin’s aim to prove that Russia is an equal actor in the international arena and show it to the people in his country.

Hypothesis 2: Russia provide information warfare directed at its own citizens, which aims, in this case, are manipulations of population’s moods and establishment of a (favorable) image of the leader of the country and to show that the negotiations were more than successful for Russian Federation.

Verification of the stated expectations requires empirical evidences followed this section.

Findings

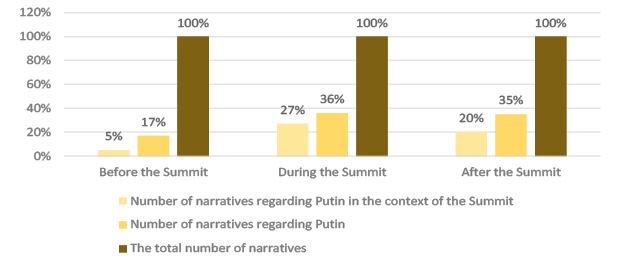

The results supported both hypotheses. Indeed, Russian media – ‘Channel one’ – devoted considerable amount of broadcasting time to President Putin within June 27–July 22. The highest number of narratives regarding Putin happened during the Summit (36%) and immediately thereafter (35%) that Figure 1 presents. Such a low frequency of Putin’s agenda (17%) and the Summit agenda before the meeting (June 27–July 15) may be explained by a concurrent existence of another agenda at the same period in form of ‘FIFA World Cup 2018’ (more than 40%). Other issues were mostly related to internal or external policy and different topics, and are about 20% each. During the day of Summit media narratives were focused on football agenda (44%), however, the meeting was considered to be the most important topic according to the presenter. Internal and external policy remained to be the issue on the top of the discussion (about 40%) after the event.

Figure 1. Frequency of narratives of ‘Putin’ mention.

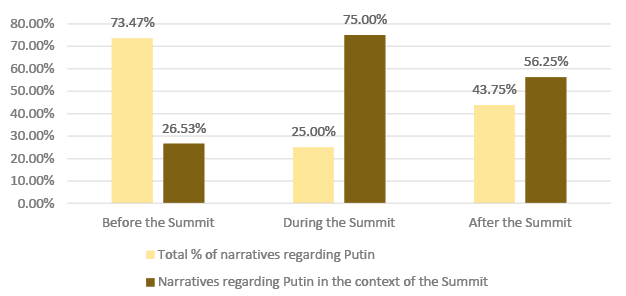

With regard to the frequency referred to falls under mention of Putin in the context of US–Russia Summit in Helsinki it may be stated that Putin’s agenda was set in form of the presidential meeting and it was occurred more often during (75%) and after (56%) the Summit. However, he appeared only in 26% of cases before the negotiations (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2. Mention of Putin in the context of US-Russia Summit.

About 67,6% of information about Putin or his activities in the context of the Summit is found at the beginning (and 32,3% in the middle) of the program, reflecting the importance of the narratives presented the President and the Summit agenda.

Assessment of the meeting in Helsinki by ‘Time’ program one can find very successful. The Russian media was assuring its viewers that Russian-American relationships may undergo a period of a political thaw (50%), rapprochement (29%) and productive dialog (26%). Failure (2,94%) was used in Trump’s context only. The Table 1 below demonstrates the most popular approach visualizing the attitude of the workers of ‘Time’ program. The red colour means the most cumulative elements.

Table 1. Assessment of the Summit.

| Success | 17,65% |

| Political thaw | 50% |

| Partnership | 2,94% |

| Rapprochement | 29,41% |

| Productive dialog | 26,47% |

| Rivalry | 0% |

| Failure | 2,94% |

| No comment | 23,53% |

| Other | 20,59% |

Table 2 presents expanded version of the previous one with the reference to most repeated statements of the Russian media according each period of the agenda. ‘Время’ program expected political thaw (30%) in advance of the meeting. It was strongly insisted besides on rapprochement and productive dialog (100%) during the negotiations and on political thaw (44%) again instantly after they were over. Most frequent phrases that describe the attitude of ‘Channel one’ precisely are: “the main event of the summer and even the year” (Vremia, June 27–July 1), “impetus for the development of bilateral relations” (Vremia, June 27), “first full-format meeting of the two countries” (Vremia, July 4), “the meeting is doomed to public success” (Vremia, July 5), “the meeting with the Russian leader may be easier than negotiations with the Prime Minister of Great Britain” (Vremia, July 10), “the meeting is important” (Vremia, July 13), “getting along with Russia would be a good thing, not a bad thing” (Vremia, July 15), “this is a tipping point” (Vremia, July 16), “it is a success” (Vremia, July 18), “the most important foreign policy event […] it’s good that the dialogue has begun” (Vremia, July 19), “negotiations in Helsinki” (Vremia, July 21). The red colour means the most cumulative elements.

Table 2. Attitude reflection of Russian media towards the Summit.

| Before | During | After | |

| Success | 0% | 33,3% | 27,8% |

| Political thaw | 30% | 100% | 44,4% |

| Partnership | 0% | 0% | 5,6% |

| Rapprochement | 15% | 100% | 22,2% |

| Productive dialog | 5% | 100% | 27,8% |

| Rivalry | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Failure | 5% | 0% | 0% |

| No comment | 15% | 0% | 27,8% |

| Other | 25% | 0% | 11,1% |

Media coverage of Putin is worth special attention. It was supposed that the media would use different connotation linked to his person including the name, occupation, position, institution or location (city and state). According to the results (see Table 3) the president usually was called as Vladimir Putin (73%), Putin (23,5%), Leader (26,5%), President or President Vladimir Putin (14,7%). The red colour means the most cumulative elements.

Table 3. How Putin was mentioned.

| Vladimir Putin | 73,5% |

| Putin | 23,5% |

| President | 14,7% |

| President Vladimir Putin | 14,7% |

| President Putin | 8,8% |

| Russia | 11,8% |

| Leader | 26,5% |

| Vladimir Vladimirovich | 0% |

| Kremlin | 2,9% |

| Head | 5,9% |

| President of Russia | 14,7% |

| Moscow | 2,9% |

| Rival | 2,9% |

| None | 2,9% |

Table 4 refers to the frequency of how many times for the agenda existence Putin was mentioned and how exactly he was called by the media. The table has a link to the Figure 2 as well and gives a more detailed explanation to appearance of the Putin’s image in the context of the Summit agenda. Turning to the suggestion of existence of another agenda at the same period one can see the statistics of low frequency of Putin mention the event before (as Vladimir Putin – 35%, President Vladimir Putin – 25%, Putin – 20%, leader – 20%) and dramatic increase in the following timeline (mostly as Vladimir Putin and Leader – 66%, and Vladimir Putin again – 83%). The red colour means the most cumulative elements.

Table 4. Frequency of calling Putin’s name.

| Before | During | After | |

| Vladimir Putin | 35% | 66,7% | 83,3% |

| Putin | 20% | 33,3% | 22,2% |

| President | 5% | 0% | 27,8% |

| President Vladimir Putin | 25% | 0% | 0% |

| President Putin | 10% | 0% | 5,6% |

| Russia | 15% | 0% | 5,6% |

| Leader | 20% | 66,7% | 0% |

| Vladimir Vladimirovich | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Kremlin | 5% | 0% | 0% |

| Head | 5% | 0% | 0% |

| President of Russia | 10% | 33,3% | 0% |

| Moscow | 0% | 33,3% | 0% |

| Rival | 0% | 0% | 5,6% |

| None | 0% | 0% | 5,6% |

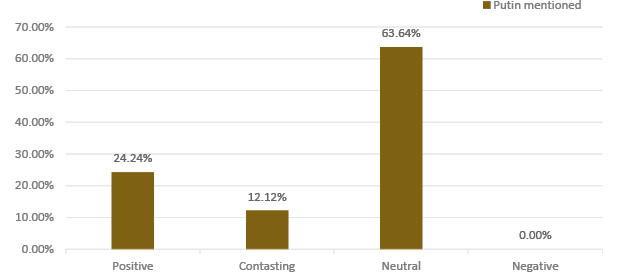

Figure 3 demonstrates the attitude of the media to the Russian president. Generally, it was expected to have the opposite outcomes due to the literature discussed in the theoretical framework. According to the results media coverage of Putin turned out to be neutral (64%) in comparison to positive (24%), contrasting (12%) and negative (0%) determinations. This may be explained by using the concept of contrasting the images between the characters appeared on the screen. Put differently, Putin’s image is not being created directly by the media, but is created in the case of comparison to somebody else (defamation of Trump would be the best example) or in the context of an event and its problems (e.g. Syria or Ukraine issues). Furthermore, lack of negative narratives related directly to Putin is entirely to be expected results according to the hypothesis about establishment by Russian media of a (favorable) image of the leader of the country.

Figure 3. Attitude of the media to Putin.

Here it is worth noticing that in general a narrative makes its viewers to perceive the President positively, however, if one may separate a part where Putin was mentioned, it might be seen how neutral the narrative about him is. Thus, manipulations with the contrast played a great role in creating a ‘proper’ appearance of the person in the Summit case.

Achievements of the summit for Russia were mentioned by the media in 44% of the narratives of which 73% concerned about Russia’s interest. Among them are the following statements: “Today’s negotiations reflected our joint wish […] to redress this negative situation and bilateral relationship, outline the first steps for improving this relationship to restore the acceptable level of trust and going back to the previous level of interaction on all mutual interests issues. […] Russia and the United States apparently can act proactively and take – assume the leadership on this issue and organize the interaction to overcome humanitarian crisis and help Syrian refugees to go back to their homes” (“Transcript: Trump And Putin’s Joint Press Conference”, 2018; Putin’s speech at press conference after the negotiations, Vremia, July 16), “Constructive dialogue between the United States and Russia affords the opportunity to open new pathways toward peace and stability in our world” (“Transcript: Trump And Putin’s Joint Press Conference”, 2018; Trump’s speech at press conference after the negotiations, Vremia, July 16). At the same time both sides reached an understanding on the implementation of the agreements of the presidents of Russia and the United States in the field of international security, on the settlement of the Syrian conflict taking into account the interests of Israel and the humanitarian crisis in the country organizing ‘Centre for the Reception, Allocation and Accommodation of Refugees’ by Russia. Putin also added that Russia is ready to save gas transit through the territory of Ukraine if the disputed issues are resolved in the Stockholm Arbitration.

The US–Russia meeting agenda is a little different than the way the Putin’s image was introduced by the media. Since the context is significant for the purpose of creating a good image it can be assumed that the Summit couldn’t help showing the negotiations were more than successful for Russian Federation. The meeting with Trump in itself is a demonstration of equality between the states, hence, confirmation of power and confidence on the international arena and within Russian society.

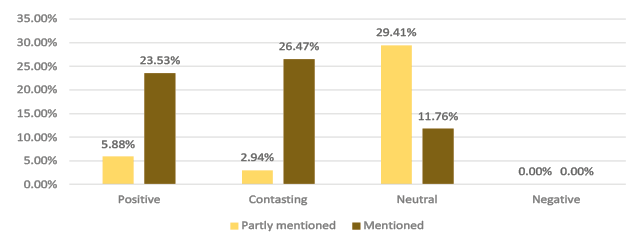

Figure 4. Attitude of the media to the Summit.

Figure 4 illustrates a media approach to the Trump-Putin negotiations. In the situation when the narrative concerned the Summit directly there can be seen contrasting (26%) and positive (23%) attitude of ‘Time’ TV program. Contrasting in this case means in-between a state of negative (e.g. Trump’s issue) and neutral (e.g. Putin’s interview) or negative and positive: “This meeting was prepared for a long time by both sides of the ocean. […] To discuss the latest nuances, National Security Advisor, John Bolton, arrived in Moscow. In the White House, he has a reputation as a ‘war hawk’ and has repeatedly made belligerent statements against Russia. Some time ago, he threatened people disliked by Washington [...], but at the meeting with Putin, the John Bolton’s rhetoric was completely different […] (Putin’s words:) ‘Russian-American relationships are not in a good conditions […] I assume once again, it is largely the result of a sharp domestic political struggle in the United States itself, but your (Bolton’s) visit to Moscow gives us hope [...] to restore full-format relations” (Vremia, July 1), “it’s good for American presidents to meet with adversaries, to clarify differences and resolve disputes. But when President Trump sits down with President Vladimir Putin of Russia in Finland next month, it will be a meeting of kindred spirits” (quotation of ‘The New York Times’ in ‘Vremia’, July 5), “Summit in the background of Trump’s developing trade wars with European allies. […] bargaining terms may and should be European sanctions against the Russian Federation, because for Europe sanctions are a encumbrance, and for the United States are not, by and large” (Vremia, July 5), “[Trump and Putin] shook their hands. Trump is being known for forcefully pulling on the hand he’s shaking didn’t even bother to do it in case of Putin” (Vremia, July 16), “nothing has been known about the active support of Russian efforts to restore the country and the return of refugees from Europe and the United States so far, but the general approval is already a success” (Vremia, July 20).

Table 5 below presents outcomes of manipulations’ methods the analysis carried out. It is worth mentioning that both categories – language and psychological – interact in an effective, coordinated and coherent manner. The red colour means the most cumulative elements.

Table 5. Methods of manipulations.

| Language | Psychological | ||

| Attaching epithets | 52,9% | Halo effect | 70,6% |

| Invoking the authorities | 64,7% | Framing effect | 79,4% |

| Bandwagon effect | 32,4% | Self-serving bias | 17,6% |

| Card stacking | 58,8% | Assertion | 47,1% |

| The method of creating “political myths” | 41,18% | Dramatization | 38,2% |

| Semantic convergence method | 55,8% | None | 2,9% |

| None | 2,9% | – | – |

Framing effect (79%) often appears at the beginning of the narrative (e.g. the EU is afraid of the Summit’s consequences in Vremia, July 5, 11, 12, 13) to shape the main idea reflected in the different way using some methods of manipulations listed below. Halo effect (71%) helps to create the proper vision of the subject also including language method of attaching epithets (53%) to enhance the effects: “[the Summit had a] tremendous significance” (Vremia, July 5), “the main event of the year” (Vremia, July 1), “such a meeting ought to succeed”, “so called allies [USA]”, “[Trump] is insufficiently prepared” (Vremia, July 5), “unpredictable Trump” (Vremia, July 11), “everyone is armed [in the USA]” (Vremia, July 17), “national bullying” (Vremia, July 18), “anti-Russian hysteria” (Vremia, July 19) etc. It is frequently happened that command of detail follows without elaboration (assertion – 47%): “in fact, anti-Russian sanctions imposed on Europe are a tool for competitive suppression of Europe by the US” (Vremia, July 5), “few may have not liked the requirement to shell out” (Vremia, July 12), “non-royal reception of Trump” (Vremia, July 13), “more than a hundred militants refused to leave and stayed in the city […]; because people believed their government” (Vremia, July 17), “over 1.5 million people are ready to return to Syria” (Vremia, July 21).

Another salient feature of broadcasting the narratives is method called invoking the authorities (used 65%) presented in form of citation of different actors (see also Table 6): politicians and authorities (e.g. John Bolton, Angela Merkel, Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin, Theresa May, Foreign Ministry), experts (e.g. James Jatras, specialist in international relations; Andrey Kortunov, political scientist; Veniamin Popov, from MGIMO; Filip Dewinter, political scientist) and media (e.g. FOX News, CNN, Russia Today, The New York Times, The Guardian, The Sun, The Washington Post).

Table 6. Source of manipulations.

| Journalist | 67,7% |

| Presenter | 88,2% |

| Interviewer | 8,8% |

| Putin | 17,7% |

| People | 17,7% |

| Expert | 23,5% |

| Others | 23,5% |

In each case the statements provided by any of these actors are often taken completely out of context: the citation may refer to different topic (e.g. part of Trump’s interview on FOX News (“Trump: ‘Phony’ Mueller Probe”, 2018) about Iran issue was taken into accusation of Russia of interference in the 2016 United States elections – Vremia, July 17) and an article or a report may present entirely different information (e.g. Rasmussen reports survey about possibility of Civil War 2 in the USA (Rasmussen Reports, 2018): the data was presented in the way as if the majority are about to believe it might happen in the future – Vremia, July 17). The problem with that is nobody is likely to check the truthfulness of the received data.

An interesting element of manipulations might be the method of card stacking (59%). Its frequency is relatively high and it mostly relates to the context of Trump’s defamation. Since the image of Trump was not the purpose of this paper the data about his personality wasn’t collected in systematic way. However, it was already mentioned that this technique is used for contrasting the images between the characters appeared on the screen. Hence, Putin wasn’t described by the media directly, but in the way of semantic convergence method (56%) that allows to make comparative conclusions about its effect on the Summit agenda and Putin’s image perceptions. Before the Presidents’ meeting, for instance, Donald Trump and his visit to the EU was the main focus of the Russian media (Trump’s criticism towards his European allies and the EU concerns about any agreement between the US and RF). During the day of the Summit Putin was described in a contrasting manner between Trump criticized by media worldwide and neutral or semi-positive position of Russian President (he himself considers Trump to be a good speaker – Vremia, July 16).

At the end of the narrative a journalist (68%) or a presenter (88%) usually concludes the conducted reasoning as the logical truth (see Table 6). In this context, media workers should be given their due for doing their job very professionally as television remains the main source of the information (70%) with parallel percentage of credibility to the media of about 51% (Информационные источники, 2018).

Conclusions

The present article was aimed to analyze the influence of information warfare directed to a state’s own citizens in the form of media agenda-setting of an issue. Since television is considered to be the most primary source of information for 73% population in Russia, it was decided to select one the most popular TV channel. The ‘Channel one’ was chosen according to the survey of the news resources’ popularity, where percentage of viewers is 72%, hence, where ‘Time’ is the top-ranked news program. On the chosen example the study was oriented mainly to content analysis of how Russian media framed the US–Russia Summit and the medial image of Putin for Russians in the context of the meeting. It is worth mentioning that the Summit media coverage was analyzed from the perspective of only one TV channel, which, however, is considered to be the most popular in Russia. There are still needs for surveys of the reflections of the target audience to approve evidences are concluded in this article. Since this article is a case study of one particular event it does not cover a wide spectrum of using methods of manipulation at the example of other issues. However, there are a lot of studies related to the issue of Russian propaganda and the authors managed to prove that the media uses propaganda techniques (Gerber & Zavisca, 2016; Lucas & Pomeranzev, 2016; Paul & Matthews, 2016). The last but not least: as it is known that Putin’s rating is going down since the recent elections, the agenda of the Summit didn’t seem to impact to the rating strongly (but the fall slowed and was relatively fixed). Nevertheless, it can be explain by existence of other agendas at the same time (pension reform, for example), which affected badly his position.

Drawing on theoretical framework of the related literature the main purpose of this article was founded on the following assumptions that: a) the US–Russian Summit in Helsinki (2018) should have served as another reason for Putin’s aim to prove that Russia is an equal actor in the international arena and show it to the people in his country; b) Russia provide information warfare directed at its own citizens, which aims, in this case, are manipulations of population’s moods and establishment of a (favorable) image of the leader of the country and to show that the negotiations were more than successful for Russian Federation. Indeed, the research showed the presence of manipulation methods of information a Russian viewer receive every day of the selected period. According to particular findings it can be emphasized that the Summit agenda and image of Vladimir Putin were created by using manipulation tools to convince consignees of positive perception of Russian leader.

References

Ader, C. (1995). A Longitudinal Study of Agenda Setting for the Issue of Environmental Pollution. SAGE Journals, 72(2), 300–311.

Berzins, J. (2014). Russia’s New Generation Warfare in Ukraine: Implications for Latvian Defense Policy, National Defense Academy of Latvia, Policy Paper, 2, 1–13.

Borecki, R. (1987). Propaganda a polityka, przeł. I. Zawadzka. Warszawa: Centralny Ośrodek Metodyczny Studiów Nauk Politycznych.

Campbell, W.K., Sedikides, C. (1999). Self-threat magnifies the self-serving bias: A meta-analytic integration. Review of General Psychology, 3(1), 23–43.

Cohen, B. (1963). The press and foreign policy. New York: Harcourt.

Cohen, J., Weimann, G. (2000). Cultivation Revisited: Some Genres Have Some Effects on Some Viewers. Communication Reports, 13(2), 99.

Cohen, W. (1997, May). Report of the Quadrennial Defense. Retrieved form https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/32542/qdr97.pdf (August 2018).

Darczewska, J. (2015). Wojna informacyjna Rosji z Zachodem. Nowe wyzwanie?, Przegląd Bezpieczeństwa Wewnętrznego – wydanie specjalnie.

Deutsch, K. (1964). External Involvement in Internal Wars. In: H. Eckenstein, Internal War: Problems and Approaches, New York: Free Press of Glencoe, 100–110.

DeYoung, K. (2018, July 20). Russia continues to shape narrative of Helsinki summit. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/russia-continues-to-shape-narrative-of-helsinki-summit/2018/07/20/3ea54a98-8c40-11e8-a345-a1bf7847b375_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.85fc285285e8 (August 2018).

Druckman, J. (2001). On the Limits of Framing Effects: Who Can Frame? The Journal of Politics, 63(4), 1041–1066.

Entman, R. (1993). Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58.

EU vs. Disinfo. (2017, September). Get ready for pro-Kremlin tinnitus. Retrieved from https://euvsdisinfo.eu/get-ready-for-pro-kremlin-tinnitus (September 2018)

EU vs. Disinfo. (2018, September). Russia as a Target of Russian Disinformation. Retrieved from https://euvsdisinfo.eu/russia-as-a-target-of-russian-disinformation (September 2018).

EU vs. Disinfo. (2018, September). Someone Said That the Referendum in Crimea was Legitimate. Retrieved from https://euvsdisinfo.eu/someone-said-that-the-referendum-in-crimea-was-legitimate (September 2018).

Feeley, T., O’Mally, A., Covert, J. (2016). Content Analysis of Organ Donation Stories Printed in U.S. Newspapers: Application of Newsworthiness. Health Communication, 31, 495–503

FOX News Insider. (2018, July 16). Trump: ‘Phony’ Mueller Probe Is Driving a ‘Wedge’ Between Us and Russia. Retrieved from http://insider.foxnews.com/2018/07/16/donald-trump-russia-putin-summit-robert-mueller-could-meet-kremlin-investigation (September 2018).

Freeland, A. (2012). An Overview of Agenda Setting Theory in Mass Communications. University of North Texas. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/3355260/An_Overview_of_Agenda_Setting_Theory_in_Mass_Communications?source=swp_share (September 2018).

Gamson, W.A. (1989). News as Framing: Comments on Graber. American Behavioral Scientist, 33, 157–166.

Gamson, W.A., Modigliani, A. (1987). The Changing Culture of Affirmative Action. In: R.G. Braungart M.M. Braungart (ed.), Research in Political Sociology, 137–177, Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Gates, R. (2010, February). Quadrennial Defense Review Report. Retrieved form http://archive.defense.gov/qdr/QDR%20as%20of%2029JAN10%201600.pdf (September 2018).

Gerber, T., Zavisca, J. (2016). Does Russian Propaganda Work?. The Washington Quarterly, 39(2), 79–98.

Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., Signorielli, N. (1994). Growing up with television: The cultivation perspective. In: M. Morgan, Against the mainstream: The selected works of George Gerbner (93–213). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Jackson-Beeck, M., Jeffries-Fox, S., Signorielli, N. (1978). Cultural indicators violence profile no. 9. Journal of Communication, 28(3), 176–207.

Gronowska-Starzeńska, A. (2017). Walka informacyjna – wybrane problemy w ujęciu cybernetycznym, Zeszyty Naukowe ASzWoj, 4(109), 36–45.

Hoffman, F. (2007). Conflict in the 21st century: Rise of the Hybrid Wars, Arlington, 18-25, http://www.potomacinstitute.org/images/stories/publications/potomac_hybridwar_0108.pdf (September 2018).

Iyengar, S., Simon, A. (1993). News Coverage of the Gulf Crisis and Public Opinion. A Study of Agenda-Setting, Priming, and Framing. SAGE Journals, 20(3), 365–383.

Kazun, A. (2017). Agenda-Setting in Russian Media. Higher School of Economics Research Paper No. WP BRP 49/PS/2017. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3032920 (September 2018).

Lachman, S., Bass, A. (1985, November). A Direct Study of Halo Effect. Journal of Psychology, 119(6), 535–540.

Levada-Center (Левада-центр). (2018). Информационные источники. Retrieved from https://www.levada.ru/2018/04/18/informatsionnye-istochniki/ (September 2018).

Levada-Center (Левада-центр). (2018). Каналы информации. Retrieved from https://www.levada.ru/2018/09/13/kanaly-informatsii/ (September 2018).

Levada-Center (Левада-центр). (2018). The credibility of the media and willingness to speak out. Retrieved from: https://www.levada.ru/cp/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Doverie-novostyam_tab..pdf (12.10.2018).

Lind, W., Nightengale, K., Schmitt J., Sutton J., Wilson, G. (1989). The Changing Face of War: Into the Fourth Generation, Marine Corps Gazette 73, 10; ProQuest Direct Complete, 22–26.

Lipman, M. (2009). Media Manipulation and Political Control in Russia, Carnegie Moscow Center. Available at: https://carnegie.ru/2009/02/03/media-manipulation-and-political-control-in-russia-pub-37199 (September 2018).

Lippmann, W. (1922). Public opinion. New York: Harcourt.

Lucas, E., Pomeranzev, P. (2016). Winning the Information War: Techniques and Counter-strategies to Russian Propaganda in Central and Eastern Europe. Center for European Policy Analysis. Report by CEPA’s Information Warfare Project in Partnership with the Legatum Institute. Available at: www.cepa.org (September 2018).

Mack, A. (1975). Why Big Nations Lose Small Wars: The Politics of Asymmetric Conflict, World Politics, 27(02), 175–200.

McCombs, M., Shaw, D., Weaver, D. (1997). Communication and Democracy: Exploring the Intellectual Frontiers in Agenda-Setting Theory. Mahwah: New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

McQuail, D. (1994). Mass Communication Theory: An Introduction. 3 ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mikelionis, L. (2018, July 13). Democrats assail Trump’s remarks on Germany’s reliance on Russia despite Kerry, Biden issuing similar concerns. Fox News. Retrieved from https://www.foxnews.com/politics/democrats-assail-trumps-remarks-on-germanys-reliance-on-russia-despite-kerry-biden-issuing-similar-concerns (September 2018).

Mumford, A. (2013). Proxy Warfare and the Future of Conflict. The RUSI Journal, 156(2), 40–46.

Nemeth, W. (2002). Future war and Chechnya: a case for hybrid warfare. Monterey, CA, 49-63, Retrieved from https://calhoun.nps.edu/bitstream/handle/10945/5865/02Jun_Nemeth.pdf (September 2018).

O’Byrne, D. (2003). Human Rights. An Introduction. Harlow, England; New York: Longman.

Paul, C., Matthews, M. (2016). The Russian “Firehose of Falsehood” Propaganda Model. RAND Corporation. Retrieved from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE198.html (September 2018).

Plous, S. (1993). The psychology of judgment and decision making. New York, NY, England: Mcgraw-Hill Book Company.

Polyakova, A. (2018, July 12). What Putin wants in Helsinki. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2018/07/12/what-putin-wants-in-helsinki/ (September 2018).

Price, V., Tewksbury, D. (1997). News Values and Public Opinion: A Theoretical Account of Media Priming and Framing. In: G.A. Barett, F.J. Boster (eds). Progress in Communication Sciences: Advances in Persuasion. 173–212, Greenwich, CT: Ablex.

Rasmussen Reports. (2018, June 27). 31% Think U.S. Civil War Likely Soon. Retrieved from http://www.rasmussenreports.com/public_content/politics/general_politics/june_2018/31_think_u_s_civil_war_likely_soon (September 2018).

Riddle, K. (2009). Cultivation Theory Revisited: The Impact of Childhood Television Viewing Levels on Social Reality Beliefs and Construct Accessibility in Adulthood (Conference Papers). International Communication Association, 1–29.

Rogers, E.M., Dearing, J.W. (1988). Agenda-setting research: Where has it been? Where is it going? Communication Yearbook, 11, 555–594.

Russian Analytical Digest. (2013, February 21). The Russian Media Landscape, No. 123.

Sarkesian, S. (1985). Low Intensity Conflict: Concepts, Principles, and Policy Guidelines. Air University Review.

Simons, G. (2016). Stability and Change in Putin’s Political Image During the 2000 and 2012 Presidential Elections: Putin 1.0 and Putin 2.0? Journal of Political Marketing, 15, 149–170

Skoneczny, Ł. (2015). Wojna hybrydowa – wyzwanie przyszłości? Wybrane zagadnienia, Przegląd Bezpieczeństwa Wewnętrznego, wyd. specjalne.

Szalkiewicz, W. (2014). Praktyki manipulacyjne w polskich kampaniach wyborczych. Kraków–Legionowo: edu-Libri.

Transcript: Trump And Putin’s Joint Press Conference. (2018, July 16). National Public Radio. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2018/07/16/629462401/transcript-president-trump-and-russian-president-putins-joint-press-conference?t=1539689110973 (September 2018).

Vinogradova, N., Denisova, S. (2018). A Quantitative Analysis of the Image of Russia in the AsiaPacific Region Media. European Research Studies Journal, XXI(1), 555–569.

Walgrave, S., Van Aelst, P. (2006). The contingency of the mass media’s political agenda setting power: Toward a preliminary theory. Journal of Communication, 56, 88–109.

Weaver, D., McCombs, M., Spellman, C. (1975). Watergate and the Media. A Case Study of Agenda-Setting. SAGE Journals, 3(4), 458–472.

Wintour, P. (2018, July 17). Helsinki summit: what did Trump and Putin agree? The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jul/17/helsinki-summit-what-did-trump-and-putin-agree (September 2018).

Wojtkowski, Ł. (2010). Agenda-Setting Versus Freedom of Speech, Polish Political Science, XXXIX, 241–252.

Wrzosek, M. (2012). Dezinformacja – skuteczny element walka informacyjnej, Zeszyty Naukowe AON, 2(87). Retrieved from http://yadda.icm.edu.pl/yadda/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-75b59b93-53e3-407c-84c2-9506be837ce0 (September 2018).

Wrzosek, M. (2015). Trzy wymiary wojny hybrydowej na Ukrainie. Kwartalnik Bellona, 3, 33–46.

Герасимов, В. (2013, Февраль). Ценность науки в предвидении. Военно-промышленный курьер. (Gerasimov, V. (2013, February). The Value of Science Is in the Foresight). Available at: https://www.vpk-news.ru/articles/14632 (September 2018).

Манойло, А. (2015). Гибридные войны и цветные революции в мировой политике. Право и политика, 7, 918–920. Retrieved from https://istina.msu.ru/publications/article/10584094 (September 2018).

Полозов, В. (2018). Сравнительный анализ политических имиджей на примере В.В. Путина и Д. Трампа. Студенческий форум, 10(31), Available at: https://nauchforum.ru/journal/stud/31/36110 (September 2018).

Пухов, Р. (2015, May 29). Миф о «гибридной войне». Независимое военное обозрение. Retrieved from http://nvo.ng.ru/realty/2015-05-29/1_war.html (September 2018).

Appendix

General analysis

Title: …

The date of the television episode broadcast:

Duration of selected narrative: …

The total number of narratives: …

Number of narratives regarding Putin: …

Number of narratives regarding Summit: …

Source: …

Analysis of the selected narrative

Timeline: …

Category 1. Image of Putin

1.Is it said about the Summit?

- Yes

- No

- Partly mentioned

2.If yes, it was described as: …

3.Attitude of the media:

- Positive

- Contrasting

- Neutral

- Negative

4.Putin was mentioned:

- Yes

- No

5.Putin was mentioned as:

- Vladimir Putin

- Putin

- President

- President Vladimir Putin

- President Putin

- Russia

- Leader

- Vladimir Vladimirovich

- Kremlin

- Head

- President of Russia

- Moscow

- Rival

- None

6.Putin was described as: …

7.Attitude of the media:

- Positive

- Contrasting

- Neutral

- Negative

8.In the context of what topic was Putin mentioned? …

9.Is it said about Russia’s interest?

- Yes

- No

10.Is it said about Putin’s achievements?

- Yes

- No

11.What achievements of the summit for Russia were mentioned by the media? …

12.Does Putin himself talk about the issue?

- Yes

- No

13.Assessment of the meeting by the media:

- Success

- Political thaw

- Partnership

- Rapprochement

- Productive dialog

- Rivalry

- Failure

- No comment

- Other …

14.Regarding to the previous question what was the topic? …

15.The image was creating:

- Before the summit (16.07.2018)

- During the summit (16.07.2018)

- After the summit (16.07.2018)

16.The information about Putin or his activities in the context of the Summit is found:

- At the beginning

- In the middle

- At the end

Category 2. Methods of manipulations

17.Language

- Attaching epithets

- Invoking the authorities

- Bandwagon effect

- Card stacking

- The method of creating “political myths”

- Semantic convergence method

- None

18.Psychological

- Halo effect

- Framing effect

- Self-serving bias

- Assertion

- Dramatization

- None

Category 3. Source of manipulations

- Journalist

- Presenter

- Interviewer

- Putin

- People

- Expert

- Others